In the preface to his 1972 short story collection, Girls

at War, Chinua Achebe commented that it was “something

of a shock” that his earliest stories were published

“as long as twenty years ago” and he could therefore

no longer be described as “new”. Four decades

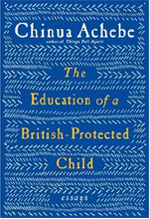

later, his volume of essays The Education of a British-Protected Child, published in the UK this month,

is both familiar and still fresh, revisiting expected themes

and yet charming the reader anew.

Controversially hailed as one

of the founding fathers of African literature, Achebe’s

career spans a period of radical change, from the optimism

of Nigerian Independence to transatlantic elation at Obama’s

election. Things Fall Apart has inspired five generations

of adults and schoolchildren. Looking back at these years,

Achebe comments: “I wanted very much to shine the torch

of variety and of difference on the experiences my life has

served up to me, illuminating what it is that unites my writing

and my personal life.” The resulting volume brings

together pieces dating from 1988 to 2009.

The title essay of the collection

recounts the young writer’s realisation on receiving

his first passport, that he was defined as a “British

Protected Person”. Of the disingenuous patronage of

colonialism Achebe makes it clear straight away he will offer

“only cons”. Not unexpected for anyone familiar with his work. The

statement though is tempered by a pledge to explore the middle

ground – antithetical to the fanaticism Achebe terms

the “One Way, One Truth, One Life menace”. The

nuanced space he roams around in this essay is that of his

education at Government College Umuahia, a school where he

studied with a remarkable number of the incipient heroes of

African literature. He remembers with fondness his extraordinary

head teacher, a Cambridge mathematician who forbade the reading

of text books on three days a week in favour of the perusal

of novels. It is perhaps no coincidence that Achebe’s

fellow alumni included amongst others the leading poet of

his generation, Christopher Okigbo, and the writer and environmental

activist Ken Saro-Wiwa. Tragically both were to die far too

young – Okigbo fighting for Biafra, Saro-Wiwa protesting

Shell’s oppression of the Ogoni people.

The passion and commitment of

this, the first generation of internationally recognised African

writers, resonates throughout the book. Achebe describes

their heady optimism in his account of an infamous conference

at Makerere University, Uganda in ’62. Evoking debates

that still dominate the field, he recalls animated discussions

of language and identity, the endless “problem of definition”.

On the relevance of literature though he is unequivocal.

Describing the advent of African literature as one of the

most beneficial explosions to rock the continent in the 60s

and 70s, he derides the “fashionable claim” that

“literature can do nothing to alter our social and political

condition” with the admonition, “of course it

can!”.

One of the most humbling and

inspiring aspects of this collection is Achebe’s enduring

belief in the relevance of literature and his public responsibilities

as a writer. In “Africa Is People” he tells the

story of a meeting of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation

and Development that he was asked to attend in 1989. Initially

rather unsure as to why he had been invited, he listened with

growing unease to the theoretical suppositions of international

economists, convinced that structural adjustment regimes merely

required time. Achebe describes his sudden realisation that

what was going on before him was “a fiction workshop, no more no less!”. Standing to take the floor, he

then addressed the room of international experts, protesting:

“Here you are spinning

your fine theories, to be tried out in your imaginary laboratories

[...] and hoping for the best. I have news for you. Africa

is not fiction. Africa is people, real people. [...] Have

you thought, really thought, of Africa as people?”

It takes the novelist to offer

the antidote to dehumanising abstraction. It is the writer

of fiction who sees the stories the others are spinning for

themselves. Achebe is an uncompromising critic of misrepresentation:

from his enduring indictment of that “thoroughgoing

racist” Joseph Conrad with his dangerously “fanciful”

descriptions of the Congo, to his fierce criticism of the

flaws of leadership in Nigerian politics. His reproaches

carry with them the urgency of someone who feels the enduring

injustices of the world personally. In “Recognitions”

the author identifies with the courage of fellow Igbo, Olaudah

Equiano, who overcame incredible odds to write the history

of his life as an enslaved person. In “Traveling White”

he recounts his experience of racial segregation on buses

in then Rhodesia. Consistently he seeks to point out how

images and myths about Africa in international circulation

remain complicit with ongoing inequalities, the culprits ranging

from thoughtlessly essentialist children’s books to

images of African suffering in the media.

But this is all beginning to

sound too earnest, an accusation it would be hard to level

at Achebe’s playful prose. Alongside serious debate,

The Education of a British-Protected Child is a monument

to Achebe’s infectious love of language, to his lively

turn of phrase and his assured self-doubt – “I

may be wrong; if so, who cares?”. The collection is

not a finely crafted and structurally coherent whole –

as the author himself points out there are gaps and repetitions.

But these essays bring together decades of fearless engagement

with literature and politics, and above all with the quirks

of personality that render each person Achebe describes ineffably

human.  |

![African Writing Online Home Page [many literatures, one voice]](http://www.african-writing.com/nine/images/logo9.png)

![]()

![]()