|

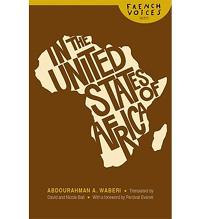

In the United States of Africa is the first translation

of Abdourahman’s fiction by David and Nicole Ball,

both seasoned literary translators. His Pays sans ombre: Nouvelles

(1994) was translated as Land without Shadows (2005)

by Jeanne Garane. Abdourahman is author of several other fictional

works written single-handedly and as co-author. His masterpiece

is undoubtedly In the United States of Africa, a novel in

which the Djiboutian writer resident in France avails himself of

the literary technique of reverse psychology to invert the accepted

prism through which we seem to perceive the world. He does so with

apparent ease. Abdourahman proves to be a master of the written

word. He wields humor, irony, sarcasm, and satire adeptly in his

attempt to debunk the often unquestionable clichés and stereotypes

that have become the lot of Africa—a continent described severally

as: “a continent for the taking”, “the lost continent”,

“and the Dark Continent”, “a continent at risk”,

and more. The novel recounts the trajectory of Malaïka, an

French child adopted by an African, Doctor Papa, on a humanitarian

mission to Asmara. Now a young artist, Malaïka returns to the

land of her birth to trace the whereabouts of her biological mother,

and perhaps find her lost identity. Her search, laden with unknowns,

is portrayed as tortuous and revealing. She is described as an ‘angel’

on account of her decent upbringing in France: “She is graceful

as an angel, and that’s why she is called Malaïka.”(p.9)

In the United States of Africa

is a futuristic novel in which the writer turns the fortunes of

the world upside down, and invites his readers to re-imagine a world

where economic refugees and victims of social oppression escape

from the squalor of America and the slums of Europe in desperation

to seek freedom and prosperity in the United States of Africa. As

he puts it: “This is what attracts the hundreds of thousands

of wretched Euramericans subjected to a host of calamities and a

deprivation of hope.” (5) It goes without the saying that

acerbic irony is a powerful deconstructionist tool in the hands

of Abdourahman as the following statement shows: “This individual,

poor as Job on his dung heap, has never seen a trace of soap, cannot

imagine the flavor of yogurt, has no conception of the sweetness

of a fruit salad. He is a thousand miles from our most basic Sahelian

conveniences.” (4) Or this other telling one: “After

an insipid soap opera, a professor from the Kenyatta School

of European and American Studies, an eminent specialist in Africanization—the

latest fad in our universities, now setting the tone for the whole

world—claims that the United States of Africa can no longer

accommodate all the world’s poor.”(6)

Abdourahman’s ambivalent use

of language is evident throughout the narrative. In a bid to translate

anger and despondency into the written word, he has no compunction

about resorting to vulgarity for the purpose of effective communication:

“In short, they are introducing the Third World right up the

anus of the United States of Africa.”(8) This novel is a poignant

depiction of the plight of the proletariat of the First World whose

very survival depends on government bailouts, referred to as ‘food

stamps’ in the United States of America. “It is a tale

that can make a family forget the absent father, always wandering

off or between odd jobs…who holds the house together by means

of federal welfare checks and various sacrifices” (9-10) This

text is a satiric derision of the fallacy of the American dream:

“Two men in quest of the African dream, seeking manioc and

fresh water. Sheriff Ouedraogo promises to spare the life of the

one who kills the other at sunset.”(19). Tongue in

cheek, the novelist laments the fate of African immigrants subjected

to all forms of ignominies in the Western world: “Not a day

goes by without new cases of disappearances, illegal immigrants

arrested and neutralized for good, illegal workers sent to meet

their maker in less time than it takes to light a cigarette.”(20)

In the United States of Africa

is captivating in several respects but the quality that captures

the reader’s attention the most is the novelist recourse to

the theme of exile as a thread that holds his narrative together:

“The tiny elite was the first to clear out, and every youngster’s

dream is to leave and go into exile.” (14).The problematic

strife with double exile (physical and psychological) seems to be

a leitmotif in Abdourahman’s text. In this novel, psychological

exile is seen to be as deleterious as physical displacement: “He’s

gone on a journey inside himself, you think… He’s really

gone. Where He doesn’t know…” (23) Abdourahman

employs sagacious words to adumbrate on this haunting theme: “One’s

birthplace is only an accident; you choose your true homeland with

your body and heart. You love it all your life or you leave it alone.”(10)

It is hard to ignore the novelist’s attempt to fictionalize

his own existential travails in the world of exile. In writing his

tale of exile, Abdourahman turns the tables topsy-turvy as this

statement clearly indicates: “Today even more than yesterday,

our African lands attract all kinds of people crushed by poverty:

trollops with their feet powdered by the dust of exodus; opponents

of their regimes with a ruined conscience; mangy kids with pulmonary

diseases; bony, shriveled old people. “(15) Abdourahman’s

text is a double-edged trenchant weapon; it chides the predator

and the prey with the same breath. It decries the tribulations engendered

by xenophobic tendencies: “They begin by setting up security

perimeters in big cities, investigate at length before tackling

lawless zones, shady hotels, guerilla camps, bordellos, and shebeens

for illegal immigrants.”(46)

In the United States of Africa

is a tale of the underdevelopment of Africa by Western powers. It

is a laudation of the material and intellectual wealth of pre-colonial

Africa: “Ever since Emperor Kankan Moussa, the ruler of the

ancient Empire of Mali, one of the most prestigious empires of our

federation, made a pilgrimage to Mecca in 1324 scattering gold along

the way, all the wretched of the earth have their eyes fixed on

our felicity.”(15) The writer underscores the fact that Africa

was not a tabula rasa devoid of prosperity before the advent of

colonialists. Intertextuality is another sharp tool that this novelist

uses for the purpose of protest. Reference to the ‘wretched

of the earth’ is undoubtedly an allusion to Frantz Fanon’s

masterpiece of the same title. Abdourahman does not stop at mere

allusions, he refers to the “neurologists in the Frantz Fanon

Institute of Blida” (27) who have “come up with a dream–making

machine that brings you whatever dreams you want while you sleep.”(28)

In a rather veiled manner, he refers to the legendary Kenyan writer

Ngugi wa Thiong’o as follows: “Following Nzila Kongolo

Wa Th’iongo (1786-1852), once so popular in the course of

the unpredictable monarch Kodjo Aemjoro, author of the classic An

Evening on the Danube…” (32) He pays tribute to

Africa’s illustrious musical virtuosos such as Miriam Makeba

(38).

The distinctive characteristic of

Abdourahman’s style is his constant recourse to code-switching

as a narrative technique. Purposeful linguistic miscegenation serves

as an effective tool for the depiction of the socio-cultural specificities

of the context in which his novel is written: “You hesitate

between a bowl of kinkeliba and a glass of bissap.”(29)

Or this other interesting one: “Maya! Pleated bubus, draped

djellabas, wraparound haiks, majestic gandouras, raffia straw, ivory

and amber, muslin and cotton, cowries and tortoise shells—vanished

all gone!”(45) The domestication of the ex-colonizer’s

language is evident here.

Abdourahman uses figurative language

for communicative expediency as this example shows: “…

his constant encouragements to the mother, who is flapping her lips

like a fish yanked out of water.”(114) Metaphors come in handy

in the narrative as this statement illustrates: “Every one

submits to the tick-tock of daily life, the order of life that pulses

with each passing second…” (30). Or this very powerful

one:” Outside, this small corner of the jungle is curling

up in the arms of the rising dawn.”(31) He employs similes

for comparative pungency: “Her great camel eyes are almost

lifeless.”(27).

Proverbs enable him to drive home

messages pregnant with meaning: “Never speak ill of the dead

is the ancient rule execrated by the hard of heart who resent those

who have just passed over to the other side.” (109) All in

all, figurative language is the palm oil with which words are eaten

in In the United States of Africa, to paraphrase another

illustrious son of Africa, Chinua Achebe.

In sum, In the United States of

Africa is the handiwork of a literary virtuoso.

Abdourahman distinguishes himself from the mainstream of Francophone

African writers through the depth of his thought processes, adroit

use of language, and skilful re-writing of history. This is a novel

steeped in innovative ideas. It is strikingly impressionistic and

didactic. The excellent translation of this fine work into English

by David and Nicole Ball cannot escape encomium.  |

|

|

|

|

|

![African Writing Online Home Page [many literatures, one voice]](http://www.african-writing.com/nine/images/logo9.png)

![]()

![]()