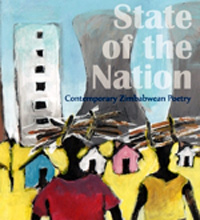

When I received this book, State of the Nation: Contemporary Zimbabwean poetry, its very pointed title

hinted that it was a project on Zimbabwe now as seen by

its various poets. I know that the state of our beloved but beleaguered

nation, Zimbabwe is now well known. The term ‘Zimbabwean crisis’

has even been spawned. Whatever way you look at it, the Zimbabwean

crisis is characterized by serious food shortages, lack of jobs,

rampant underpaying of civil servants, acute brain drain and the

general collapse of public amenities.

The causes of this crisis in Zimbabwe

fall desperately - and untidily too - between an oppositional view

and the establishment/government view. A particular incident associated

with the genesis of this crisis is the payment of hefty gratuities

to the liberation veterans from ZANLA and ZIPRA, resulting in the

first substantive fall of the Zimbabwean dollar in 1997.

In 1998 Zimbabwe intervened in the

Congo war on the side of the government of Laurent Kabila against

some rebels; this also had very negative impact on the Zimbabwean

economy. In 1999 the Zimbabwean government embarked on what its

opponents in the opposition and the West have called the ‘chaotic

land reform.’ The ‘new farmers’, as the beneficiaries

of the land reform have come to be known in Zimbabwe, have not been

able, within the interim; to produce enough for the nation to consume.

The West hit Zimbabwe with the so-called

‘targeted’ sanctions, stopping the government leadership

of Zimbabwe from traveling abroad. However in due course it became

obvious, as categorically admitted in Article IV of the Zimbabwe

Global Political Agreement document of September 2008, that the

sanctions were not necessarily targeted (as Zimbabwe cannot receive

the balance of payment from the IMF and institutions related to

Britain.)

But the Zimbabwean government has always

projected their own side of the story. First, they argued that the

international diatribe against President Mugabe was basically because

he took land from the former white settlers and distributed it to

Africans to fulfill the long-standing cause of the 1970s liberation

war. They argued further, that the British colonial policy created

the social imbalances in Zimbabwe in the first place and that the

problem in Zimbabwe was not about the rule of law since the West

has remained silent in the face of worse suppression from elsewhere

on the continent. They also claimed that the opposition was a puppet

of the West helping to further the disfranchisement of the black

people of Zimbabwe and that through the invitation and persuasion

of the opposition; the west has slammed Zimbabwe with sanctions.

Therefore, a book like State of

The Nation that boldly positions itself to look our woes in

the eye raises great expectations. Poets are seers and from them

we want to know ‘where and when the rain began to beat us.’

The editors did well to ask each poet to start with each a testimony

on what it meant to be a poet, and sometimes a Zimbabwean poet.

If you cannot read the poems, you can go for the narratives - and

sometimes, as in the cases of Emmanuel Sigauke, Nhamo Mhiripiri,

Ignatius Mabasa and Ruzvidzo Mupfudza, you can go for both.

But then I must state that this cannot

be an out-and-out book review because I know and am known to most

of the poets in here. I know the fires that begat the red brick.

Reading them is like meeting again in a new country under a new

sky. To me, most of these are both poets and people.

Probably the most unique thing about

this book is that it has poets from Zimbabwe who are still very

active. For instance Christopher Mlalazi has just won an ‘honourable

mention’ in the latest Noma awards with his book: Dancing

With Life: Tales from The Township. Noma is a greatly prized

literary award acrossl Africa. Mlalazi is also a recent winner of

NAMA, a prestigious national award. When I wrote him to congratulate

him on the Noma and pointed out that he had now won both Nama and

Noma, he wrote back: “Ngiyabonga baba… Now I

want MANA (money).” Even his poetry is like that, spontaneous

and hard hitting. In A soundless song’, a goat is

described as ‘mercilessly tearing at the petticoats of a tree

unable to flee’.

I see that Ruzvidzo Mupfudza’s

personae have not, unlike us, left the bars. In the first two poems

I see it and agree with Ruzvidzo that the region between wakefulness

and sleep is a zone in which one sees further than the eye. At that

moment, one’s sins (and those of people behind and ahead of

us) coagulate into one event. And, ah, Ruzvidzo still sees Nehanda

too!

Ignatius Mabasa’s ‘problem’

about which language to use (or not to use) is not really a problem.

Good translations (as Mabasa has done with poems like ‘Cavities’

and ‘Concrete and plastic’) will serve us well. Having

seen these poems before in the original Shona, I dare say they have

even gained extra subtlety. Consider Mai Nyevero’s ‘tan

thighs’ and how she ‘laughs like a hyena.’ I actually

see her and suffer. Harare is teeming with such women. I wonder

why Mabasa did not include a piece on baba vaNyevero. Of

course, I cannot run away from the fact that Mabasa’s strong

point is the Shona language, rendering him one of the more successful

writers of our generation with his novels, Mapenzi and Ndafa

Here?

Nhamo Mhiripiri and his wife Joyce

Mutiti are Zimbabwe's writing couple. I do not know if we have another.

We must have more. In college we saw them courting, writing and

smoking together. We wondered why they didn't fall on each other

and fight because discussions at the Students Union tended to end

in fistfights. They didn't give us that opportunity. Nhamo's pen

is conscious of ideology and theory. Joyce's is private. Today you

still see them together either at the Book Fair or the book launches

in Harare.

In his own testimony, John Eppel makes

the crudest series of claims and accusations that I have ever heard

from one of us. First, Eppel says the late Yvonne Vera, ‘like

all Shona writers with ZANU PF sympathies (was) still in too much

denial to tackle the shameful period” (of Gukurahundi) and

therefore Vera’s The Stone Virgins ‘is abject

cowardice.’ Really?

I have quietly noticed, over the years,

that John Eppel is decidedly anti Shona. Most of his bad characters

have to be Shona! Everywhere Eppel’s Shonas are senselessly

clobbering and haranguing either a white man or a hapless Ndebele.

Eppel also says that nobody includes

him in the bibliography of Zimbabwean writers. He even claims that

no contemporary of his; Mungoshi, Zimunya, Hove, Chinodya, Dangarebga,

Chirikure… ever notices him except Julius Chingono! But then

Eppel admits, strategically: ‘generalisation is a tool of

the satirist.’ Maybe.

The five poems by Charles Mungoshi

crawl all over you like ants from the underworld. As you read his

poems you have a feeling that you are working your difficult way

around boulders, towards some treasure. In 'A Kind of Drought' the

spirit is weak because one has been lied to, cheated and finally

deserted by fellow humans (and maybe especially by the leaders)

and what remains are roads, because they do not lie and trees too,

because they remain the same old faithful parents and one can do

many things with trees, including going round and round and finally

dying safely under them. And as the spirit wanders, you wish you

could come to a river.

Dambudzo Marechera’s poems, given

to the editors by one Betina Schmidt, are dedicated to Betina and

are about Betina. They remind one of Marechera’s earlier poems,

the Amelia poems. Of them Marechera once said:

‘Amelia’s presence

in the flat inspired me to write the sonnets. When she had been

in the flat and then left, I would still feel her presence, and

any item she had touched could give me the first line for a poem.

Or just the emptiness… the flat felt so completely empty,

and it is this emptiness which is all around me which I have to

grab by the collar and put into a poem.’

Nearly all the poems about exile in

this book seem to insist on the fact that exile is more dangerous

than home. These poems seem to be in the majority with the outstanding

being Chenjerai Hove’s Identity, NoViolet Bulawayo’s

Diaspora, Tinashe Mushakavanhu’s Tomorrow is long

coming, Kristina Rungano’s Alien somebody and

Amanda Hammar’s Exiles. If it is not the loneliness,

it is the anxiety or the downright confusion that comes close to

declaring that one has no country because things are currently unwell

in one’s country.

Amanda Hammar’s reminiscence

is the most uplifting narrative in this book, if you are not easily

confused. What is a Zimbabwean poet, Kizito Muchemwa once asked

Amanda Hammar in Uppsala in 2009. ‘Does location matter; does

exile/proximity make one less or more Zimbabwean; what it is we

can or should, or should not, write about, or should that even be

a question at all?’ And Amanda Hammar’s answer, which

comes after a long search is: ‘I am no longer solely defined

by my Zimbabweanness. While for some, such a condition may seem

unremarkable, for me it is both a new sensation and a big and painful

admission.’

Then you realize that this book is

also about identity. In Europe, Mushakavanhu’s persona feels

like ‘a dark presence’ and his ‘coal black hand

tightly clasping’ the long white fingers of a half-desired

white wench cause heads to turn on the streets of Europe.

In her narrative, Jennifer Armstrong

says she writes as a poet and not as a white girl. She says 'the

black white history of Zimbabwe (and Rhodesia)' has given us 'the

remarkable and highly dubious gifts of race and gender.' And her

shortest poem goes:

I don't think

my race

will win

this race

although it might

come second

It is refreshing to come across the

new voices; Beavan Tapureta, Tinashe Muchuri, Batsirai Chigama,

Josephine Muganiwa... voices associated with the spoken word at

the Book Cafe and the Zimbabwe-Germany society.

Maybe Emmanuel Sigauke's poems stand

out for not going necessarily for the 'state of the nation'. They

are not about what I need from my country and government but are

about what I did and may do. His poems as in his book Forever

Let Me Go are about personal journeys from the past to the present.

Poems about what could I have been had I not been married to you

and about the dramatic happenings in distant villages and the zinc

roofed houses that we didn't and have forgotten to build.

My worry though with most Zimbabwean

poetry since And Now The Poets Speak of 1982, is the prevalence of melancholy. Our poets

are yet to find an idiom that redeems, regardless of the well-known

woes. The poetry of Jorge Rebelo and Jose Craveirinha are an example

of poets who, while chronicling the ills of their society, reflected

also on what they should offer. They went beyond the realm of 'look

what they have done to me' and began to show 'what we have to do

about it'. I honestly believe that Zimbabwe is not the worst and

last place God made. We shall overcome.

Nevertheless, poets Tinashe Mushakavanhu

and David Nettleingham have done well to put together the first

major anthology of Zimbabwean poets writing in English since And

Now The Poets Speak. And in both cases, the poets are concerned

about the state of their nation. Mushakavanhu walks with a spring,

head up, chest out and before he talks, he rubs his hands together

like the soothsayer that he is. Somewhere in some uncomfortable

weather we once talked about how, one day, he was to become Zimbabwe’s

youngest publisher. |

![African Writing Online Home Page [many literatures, one voice]](http://www.african-writing.com/nine/images/logo9.png)

![]()

![]()