It was not a Storyteller’s moon. It was not the rotund moon

that presaged the old man’s previous visits to Ifeloju. Horned,

it only lightly kissed the leaves farthest from the dusty ground

upon which Itanpadeola’s sandaled feet trod, and it did not

wash the now-you-see-it-now-you’re-not-so-sure track to Ifeloju in an endless

glow that promised laughter and songs and sweet wine and dance.

No, it did not speak breezily of life and love and fertility and

rebirth and all other things with which the full moon was associated.

It clung desperately to the coming night; seemingly fearful it would

lose its grip and plummet like a fallen god…

That was the early moon hugging the

sky the night the Storyteller appeared. A tall weathered man with

a long face, he was thin like the staff in his right hand and feeble

like the flame of the wick lamp in his left. His arms had a multitude

of minute cuts clustered on them as if a swarm of flies wielding

miniature knives had tried to hack their way into his bloodstream.

The leather bag around his neck swung loosely as he walked. It was

the first time in his more than forty years of walking this path

that his arrival in Ifeloju would not be preceded by a full moon.

Aside from a GSM tower planted on a

distant hilltop, the village had nothing to show that the outside

world was interested in its affairs. Spared electricity, tarred

roads and modern amenities, the children walked four miles to and

from the nearest school. Some of the adults – when they were

not dyeing fabrics - walked even farther to their farms.

Ifeloju, a modest community of adire

artists, once sustained itself solely by wooing city merchants to

its dye-spattered monthly market. But the village had fallen on

hard times and many of the indigo wells had dried up. Demand had

waned for their tie-and-dye fabrics and most of the bulk buyers

from the city had switched to more affordable, higher quality alternatives.

Some young men and women followed the money to the city. Those who

remained rediscovered the supplemental attributes of hunting and

farming; and the drum of life continued to throb.

As the Storyteller approached, Foyeke

bathed in the mild rain of light from the sky. So did Tamilore and

Ifariike. The children played outdoors, holding hands, singing,

chanting, stomping their feet in eager circles, occasionally hiding

the light of youth in the soft shadows of the huts. Night games

were a ritual in Ifeloju, and even a struggling crescent moon could

not dampen their enthusiasm.

Suddenly, a voice rang out like the

clap of the town crier’s gongs in the endless cavern beneath

the Ifeloju rocks. 'The Storyteller! I see the Storyteller!'

The night held its breath, gripped

by the promise of surprise. Heads with black hair, graying hair,

tied hair, flying hair, no hair popped out of curious doorways like

little nocturnal creatures cautiously sniffing the wind before chasing

the night.

The Storyteller?

As if on cue, all the heads turned

to question the night sky. It wasn’t a storyteller’s

moon. Everyone knew Itanpadeola rode only on the back of a full

moon to Ifeloju. The moon was his guide to the village, the wine

in his gourd, his promise of seasoned songs! The shriller must have

been a child. Children were susceptible to wild imaginings in the

dark. Someone ought to send her to bed. Or was it a different storyteller?

'I see him too! I see him!'

It was a different voice now. A pair

of eyes could be fooled by the night, but two pairs of eyes? The

situation certainly called for further investigation.

The night quickly regained its voice…All

of its happy voices! The children screamed and swarmed as one in

the general direction of welcome - toward the main road that fed

the village!

The adults reacted differently. Clusters

of excitement formed as they recalled the last time the Storyteller

visited. Was it not just three markets ago? Others scampered indoors

to hastily conclude chores in progress, rouse early sleepers, grab

aso ibora in readiness for the chill that accompanies

late nights outdoors. In Ifeloju, the grownups loved tales as much

as the children and none told a tale better than the storied Itanpadeola!

His name became a chant.

Itanpadeola!

Itanpadeola!

His name became a melody that hugged

the cool night wind, slipping wirily around the contours of stained

shelters like blood through arterial routes, under the waist high

fences that confined goats and fowls, over the rusty corrugated

roof of the village Chief’s bungalow, through the wet-season-fattened

branches of trees towering above the village… onward…

Itanpadeola!

Itanpadeola!

Itanpadeola!

It was a ceaseless call emphasized

by the thump of every footfall. The whole of Ifeloju was soon possessed

by the spirit of expectation. Itanpadeola walked into their warm

reception, smiling familiarly, head and shoulders above the clamour,

a tall weary wanderer mildly bent by uncertain years. He seemed

hauntingly discernible in the weak moonlight, the dust of unimaginable

distance hiding in the folds of his skin and faded white agbada.

He walked fluidly, seeming to float above the whirlpool of children

and adults around him, stepping carefully here, touching a known

smile there, a head, a shoulder, caught in the vortex, one with

the vortex, carrying the vortex along with him as he headed for

the center of the village…

'Where is Ayandele? Someone fetch the

drum maker. Tell him Itanpadeola is here and his drums must speak

until they grow hoarse tonight.'

A bare-chested boy grabbed the message

and ran off to deliver it to Ayandele who lived on the other end

of the village where he could practice new rhythms and school apprentices

without driving the village to distraction with too much drumming.

'Itanpadeola,' hailed a man of seemingly

equally mysterious years from his perch outside a doorway, 'my brother,

you walk well.'

Caught in the vortex.

'Ogunbodede,' Itan answered, his voice

a well-oiled chunk of roasted plantain sliding down the throat,

carrying even above the wave, seeking the gaps, riding the wind.

'I see the hunter has kept well.'

One with the vortex.

'We thank the gods for their mercies.

How is the world? Is it well with world?'

Carrying the vortex along with

him…He was the vortex, whirling and twirling to their welcome

song, all bones and jutting elbows, but right where he belonged,

one with their song…One with the sing-song…

'The world grows weary like me, my

brother. Her eyes water now and her lips smart from fanning too

long the kindling of a reluctant flame. I am weary as the world.'

'But there’s always the story,

old friend… And there’s always Itanpadeola.'

'I thank you, my brother. So long

as what pleases teaches, Itanpadeola will tell the tale. I hope

the animals are still enraptured by the whiff of your gunpowder.'

'They haven’t complained to my

hearing yet.'

Both men laughed out loud at the familiar

joke. A hand tugged impatiently at Itan’s sleeve.

'Will you join us at the village square?'

'I shall be there if you promise to

pass the night under my roof.'

'Who can refuse a gift so kindly wrapped?

As always, the path from your doorstep shall lead me on at dawn.'

'You walk well, my brother.'

Itan allowed the growing crowd to suck

him in. Each crease on his forehead, each dust-layered pore, each

gray follicle of hair stored a memory of things seen that cannot

be un-seen, lives lived that cannot be un-lived…He was a vast

depository of memory, like the sea-held fish that eyes would never

see; like the shore-harbored sand that could not be numbered…He

was the rain touching leaves and skin in the most secret of places…

He was the transporter, the physical wheels of intangible culture,

the custodian of stories that transcended generations…His

father’s stories, his father’s father’s stories,

his father’s father’s father…

Unlike the typical storyteller who

lived in one community, freezing their moments and conquests in

stories and songs, Itanpadeola towered above locality. His was the

extended limb of recall transferring whole traditions between communities,

the itinerant spirit chronicling cultures and mores, the arable

imagination inventing allegories when memory stumbled.

Itan was the Storyteller of storytellers!

The vortex grew a tail, a

stream of adults who would form the protective outermost layer of

the attentive circle that would soon enclose the Storyteller near

the Odan tree in the village square. The sonorous rhythms

of Ayan’s drum had joined the singing at some point, driving

the dancing to new heights of elation. They passed the Baale’s

house. A plump woman with a child strapped to her bare back stepped

out of its doorway to join the procession, carrying a large gourd

of palm wine that foamed sprightly in the burn of the many lamps

in many hands. The Chief would be joining the storytelling soon.

The animated march stopped just short

of the Odan tree. As the crowd gathered, the tree swayed in the wind, whispering,

seemingly eager to eavesdrop on yet another tale. In the daytime,

through the seasons, the Odan was the durable host of countless meetings; tall enough to shelter many,

but not enough to call down lightning from water-logged clouds.

With the moon above struggling to light the night, it would be darker

directly under the tree, even with all the lanterns on the ground,

hooked to tree branches, held up by hands…

Only three moons had passed since the

Storyteller last stood in this same spot. He could see the questions

struggling to displace the anticipation in their eyes…Why

had he come back so soon? What changed so radically his normal cycle

of one visitation per year? What drove him to traverse the distance

tonight without his bride, the full moon?

The big smile on Itan’s face

concealed the turmoil that raged within him. He couldn’t reveal

to them how in the last few years, increasingly, the big city had

eroded his audience. The young men and women were leaving, attracted

like moths to the bright lights. Many of the villages and small

towns he performed in were now inhabited by shadows and memories.

No one wanted to farm the land anymore. They all nurtured dreams

that were too big to realise outside the city, dreams of driving

'motor car' and working in towering edifices and conducting a symphony

of mobile phones. For years on his travels, Itanpadeola had heard

stories of how cities beyond the stretch of his sandals charmed

young men and women and devoured them where no parents could salvage

their bones. They were all like streams and rivers frothing blindly

to be swallowed by the faraway sea. It was said once you answered

that call, you could never retrace your steps home.

He still remembered his foray into

the city after a lifetime of living on its periphery. Idera, his

wife – several months heavy with their only child - had finally

succumbed to the invitations from the karakata women to

investigate the wonder of city trading. Her first time in the city

had been her last. A hit-and-run, surreal like a scene from a phantasmagoric

story, her travel companions had reportedly rushed her to a clinic

near the market. It was there she breathed her last, still waiting

to be attended to by a doctor. She had pushed Itangbemi, their son,

into the world before death’s eager hands could seize him

too, giving the Storyteller two reasons to go to the big city for

the last time: a baby and a body. A wailing Iya Ibeji, one of the

women she had journeyed with, returned to tell him what had transpired.

It was she who took him to the city to fetch his living and his

dead.

Iya Ibeji, probably feeling partially

responsible for his mother’s demise, gladly raised their son

Itangbemi with her own twins and ensured he attended the public

schools with the other children. As soon as he was old enough, Itanpadeola

took him on the trail like every storyteller’s father had

before him. The experience was short-lived. He was a sickly, sensitive

child forced too soon into a harsh world and the travels were hard

on him. Itanpadeola persevered, hoping age would make him stronger.

Itangbemi, conscious of his father’s disappointment, withdrew

into a world of his own creation and began scribbling his thoughts

on little bits of paper.

In due course, Iya Ibeji informed him

that his son was unusually smart and the school was paying special

attention to his education. His son had gone away on several occasions,

to university in Ibadan on scholarship. He had even gone to Kano

for his service.

The boy remained frail into his adult

years, by which time they both came to the painful conclusion that

the itinerant lifestyle was not for him. Even if his modern education

wasn’t a deterrent, his health was. In various conversations,

Itangbemi tried to show his father the stories he was writing

in thick folders. He vowed that words on paper, once published,

would last continually and go places a traveling Storyteller’s

feet could not. Even after the source of all stories expired, a

book would thrive, he said. The Storyteller could live forever in

pages of words, like history recorded in artworks outlived the creator

and generations unborn…Forever.

Itanpadeola thought the boy had lost

his mind. It showed the jarring distance — physical and emotional

— between father and son. The Storyteller, devastated that

he was surely the last of an extended line, strayed longer on the

road, while his son warmed to the city’s call, eventually

moving away to make a home in what he knew had been his father’s

anathema since his mother’s passage. The Storyteller sought

solace in what he knew best… spreading a little joy in vanishing

villages, even if he could find none for himself…

Storytime. The people of Ifeloju parted

like thick grass beneath constant footfalls. The Baale and his counselors

had arrived. Ogunbodede was with the small entourage.

The Storyteller looked at the staff

in his hand. Old age hurt the hands now. Old age hurt everywhere,

body and mind... He couldn’t play the drum or dance like ikoto

anymore. He couldn’t grip the staff tightly either. His father

had carried one. As did his grandfather. It was a storyteller thing.

Maybe it steadied a shaky hand contemplating strangers, or readied

a trembling voice about to soften a new gathering… In the

years since his son departed for the city, the grasshoppers and

ants of eternity had descended on his mind, nibbling resolutely

away at whatever spark they could find, slowly snuffing out the

lamps and turning his mind into a long dark night. Archiving some

of his stories the same way he stored those handed down to him by

his forebears became an urgent necessity. His performances still

arrested the imagination of the crowd wherever the long limbs and

booming voice took him, but old age and the corrupting call of the

city compelled him to shrink his itinerary in response to his shrinking

audience. He liked Ifeloju.

He raised the staff and the merry-making

ceased instantly. The villagers looked at him with expectant eyes.

This was how he remembered it… How it was, how it ought to

always be; a story on a pedestal, bordered by a living audience

waiting to unravel it, longing to cradle it… His son had no

idea what he was talking about. He was already forever out here! Eternal! There could be

no better way to tell the story. What could best this repartee,

the flexibility to embellish the tale or alter it altogether in

response to spontaneous feedback, shoring the performance with music

and dance and pantomime and every creative distraction! Even if

he died, he lived on in these eyes! These lives! Didn’t he?

Ah! He still had children after all! Itanpadeola smiled bitterly, cleared his

throat and projected his voice so that it reached easily the farthest

ears.

'Gather around me like a fine garment,

children. Powder your faces with the husks of the no-sleep tree.

Fill your bellies with food enough for the long night, for we have

a ways to go. Old Itanpadeola is here to stir your mind. I am in

the mood for a tale and what a tale it is! A tale of power, greed,

adventure, triumph! Children, gather around Itanpadeola and come

hear my story. Clear your throat in readiness for song! Stretch

your limbs for the eloquence of dance! Tell me are you all here?'

The crowd responded in one voice, 'We

are!'

He placed his staff on the little stool

they had positioned for him to sit on and put his bag beside it.

'Story, oh story! My story hails from the West, the East, the South

and North. My story hails from afar where mysteries never end, and

it hails from nearby where the spirit never bends. Listen my children

and let Itanpadeola tell you of the little tree that wanted to be

a lofty forest -'

His audience burst into laughter. 'Baba,

you told us that story the last time you were here.' The villagers

thought it was a game.

'Ah, forgive me. Age has been unkind.

The mind, my friends…It plays tricks...' While his voice and

body occupied their attention, he was stumbling about in his mind,

reproaching himself for forgetting such a thing. 'Let me see, hmmm…I

don’t recall telling you about Adewuwon and the feather of

fire...'

'You did.'

'How about the python that became so

hungry-'

'-It swallowed its own tail little

by little until it disappeared.'

'Or the cloud that wanted- '

'-to steal a piece of the earth.'

'Ah, you listen well. That is one of

the reasons Ifeloju is my favorite place of all. You welcome my

stories like you welcome a steaming plate of pounded yam and egusi

soup.' The gathering laughed as Itan comically mimed eating with

his bare hands, licking the imaginary soup that dribbled down his

arm, all the way to the elbow. 'Let me see now…'

He reeled out a list of stories. They

had heard them all.

'Have I been here too many times or

have you been peeking into an old man’s mind?'

They laughed again.

'I must try harder.' He turned to

speak under his breath to the drummer who waited beside him, 'Ayan,

help an old man, will you, performer to performer? Keep them occupied

please.'

The drummer got the message and began

to rap madly on the tight leather skin of the drum around his neck,

playing to attract, playing to distract.

Itanpadeola sat down and took a long

cooling drag from the cup of palm wine someone had placed beside

him. His mind rapidly rifled through what was left of his mental

filing system for a story he could be sure had never been told at

Ifeloju. None was immediately forthcoming. It was as if he was groping

in darkness. It was time to look in the bag again…

He pulled it nearer. A dark brown

affair patched in multiple places, it was mileage frayed. He had

had it a very long time. It was his bag of no-forgetting. Every

storyteller had something similar, a way to 'store' stories outside

the mind, a mobile archive of sorts. Itanpadeola kept the most valuable

of his stories in the bag. More importantly, the bag held stories

he’d inherited from his progenitors, each carefully wrapped

in leaves like crucial pieces of a personal puzzle. While the drummer

tapped and talked the crowd into renewed frenzy, Itan’s right

hand disappeared into the bag, all the way to the elbow.

Something was wrong.

His left foot began to twitch imperceptibly

on the village square ground where the grass had been permanently

worn away by the feet of many meetings. His other arm quickly joined

the first in the bag, digging deeper, scrabbling about, fingers

feeling their way around even as the smile on his public face never

wavered. Four fingers poked out of an unexpected hole in the bottom

of the bag. A ball of sweat tracked wetly behind Itan’s right

ear.

Ogunbodede seized the moment to inch

up close to him.

'I see all is not well, my brother.'

Itan grabbed him by the shoulder and

whispered in his ear. 'My stories are gone…My father’s

stories…His father’s…They’re gone!'

His left foot was shaking visibly now and his friend placed what

seemed to be a tempering hand on it.

'May I?' Ogunbodede leaned forward

to look in the bag his friend held open for him. He reached into

the bag. He frowned. 'Is this a book?'

Itan nodded, putting the book aside.

'You have leaves in here…'

'They’re asowoje leaves.'

'Ah, the evergreen…There are

objects in some of these leaves…'

'Yes, but there should be more.' The

storyteller replied.

'You will have to tell this story

on some other night,' Ogunbodede remarked. He stood up and crossed

over to whisper in the Baale’s ear. The Chief nodded, rose

and departed with his aides. Next, Ogunbodede silenced the drums

and made an announcement, informing the villagers that Itan had

come down with the sudden fever. The performance would have to be

postponed. The villagers were disappointed, but Itanpadeola had

never failed them once in decades of hawking his tales in Ifeloju.

They accepted the explanation and dispersed, their blackened lamps

floating and vanishing in the night, fireflies blinking off to sleep.

Itan mumbled under his breath like

a doddering old man as Ogunbodede helped him to his feet. His eyes

desperately swept the ground in the dim light as he allowed himself

to be guided away. Nothing. He had no idea when the hole in the

bag let out his precious repository. He probably lost the items

on the road between Ipara and Ifeloju…or was it between Idimu

and Inumidun? Retracing his steps made no sense. He had no idea

where to begin.

He ducked his head to follow Ogunbodede

into his yard where he was led to a seat under the open skies. His

friend barked orders like the warrior descendant he was and in no

time at all, water to wash up appeared. A bowl of eba, goat

meat tumbling in ewedu soup and a palm wine gourd completed

the picture. Itan could not eat. He had much on his mind. Besides,

there was still Idera…

Ogunbodede shushed him gently. 'She

will understand, my brother. She’s not going anywhere. Eat

something first. Retrieve your strength.'

The storyteller reluctantly sipped

a little palm wine. He emptied the bag on the ground beside him

and inspected the contents. His abetiaja cap, a small cup,

the book, a knife, his orogbo chewing stick and less than half of the precious wraps… Several

of the leaves were unraveled and empty. They trembled as the night

wind teased them. The crocodile’s tooth was still in there

though. So was the kola nut fired dry in Ogun’s kiln. The

small piece of the skin of all snakes was gone. He couldn’t

see Oodua’s coronation story either. The glassy pebble from

a moss green wall at the lost lake of Apangbejo, a catfish’s

left eye, the eba odan kingmaker’s toenail, other treasures…Each piece

specially preserved to trigger the precise recall of an event or

story in its totality whenever memory stuttered…Stories ancient,

some frozen slices of immortality passed from mouth to ears to mouth

to ears by his forebears long before he was born… Gone.

Ogunbodede stopped eating in sympathy

with his friend. 'So it was the hole?'

A hole in the bag!

'When a Storyteller’s tales

begin to vacate his memory, he traps them in asowoje leaves

to preserve in a bag. While plugging holes in the mind, who knew

to anticipate holes in bags? How can such a tiny thing lose so much?'

A hole in his bag!

He sighed heavily. 'I suppose we all

must run out of time eventually...'

Ogunbodede spoke sharply, yet protectively.

'The wings of a bird never grow weary, Itanpadeola. We do not know

what evil roams the night. Take that back'

'You wish me well, my brother, but

the times are bad. If you have never traveled far enough to where

land ends and the waters begin, imagine waters swelling and falling,

rushing up to the shore like a little child to wash the memory of

footsteps off the sand…That is exactly how the last few moons

have trifled with my remembrance. My stories, my own stories

- not just the ones I inherited from my father and the ones he inherited

from his father - mine…they have been coming undone

like a raffia mat that has seen better days. I am forgetting, old

friend. Like Ifeloju’s dye pits and several of the villages

in the path of my wandering feet, my well of stories grow dry…

What you witnessed tonight has happened twice in the last one year,

with me under the glare of waiting eyes, temporarily lost for a

tale to tell. On both occasions, this bag rescued me. Once familiar

names now seem not so familiar. Yesterday, at the Bamigbopa crossroads

I have passed uncountable times, I stood there like a fool, unsure

which direction to walk. My feet and staff seized control and led

me here… I say it is old age, but old age never crippled my

father’s memory… He told his stories until the day he

died. I forget, my brother, and I am thinking time has moved on,

leaving me talking into the deaf left ear of the village idiot…I

think my story may be told. The times are bad, my brother…'

The night had grown completely silent

now. The people of Ifeloju had retired for the night. Ogunbodede

sighed like one surrendering to the crush of a mighty weight. 'Heavy

words' he said finally, 'Heavy words.'

Silence returned, quickly shattered

by a solo cricket somewhere in the compound stridently seeking to

become less forlorn.

'You know now why I’m back here

so soon…' Itanpadeola carefully returned the items on the

ground to the bag.

The two men remained quiet for a while,

listening to the night.

'Why did you never relocate to the

city?' Itan asked, a polite guest shifting the conversation to the

affairs of his host.

Ogunbodede coughed lightly, masterfully

delaying to gain time to swallow wine. 'To do what? Hunt cats and

dogs? Am I not too old for that kind of severe change?'

'It’s the noise, isn’t

it? Even from so far away, I can hear it in my head…the noise

and confusion and the crush of people…'

'The idea just never appealed to me.

I’m a bush man.'

'The world does not want to hear stories

anymore, Ogunbodede. They’re possessed by strange spirits

now…spirits I can not even begin to name. Like you, I remain

a bush man and the world has no time for people like us anymore.

Think on it…How can one out-talk their radio, out-dance their

television, out-run their motor car and in the same breath out-electrify

electricity? How?'

'The new always replaces the old,

my brother. The ears must decide of its own what to take away from

the tale. The mouth has the liberty of speech, but the luxury of

listening and understanding belong to the ears.'

Silence. The cricket served a brief

interlude, truncated by Ogunbodede. 'These ruminations you give

voice now, they have been on your mind for some time, have they

not?'

The Storyteller nodded. He stared

dully at an unlit corner of the compound. Even after all these years,

he still remembered her like the many incisions on his arms, each

tiny cut signifying a story completely told in the presence of an

audience, notes to compare with his fathers in the afterlife. She

was carved indelibly on his very being. 'I miss her, you know…

Every day.'

'I know, husband of my sister. I know.'

'She would have done a better job

of raising him.'

'She did a better job of everything

she touched.'

'Her son is somewhere in that city,

Ogunbodede. Our son.'

'Ah, that explains this conversation.

Blood will call.'

Itan contemplated the darkness a little

more. The cricket shrilled anew. He had met Iya Ibeji last week.

She had offered him a gift from the city. At first, he’d

rejected it, saying 'I doubt the city has anything of value for

people like me. Or you want to tell me my son has changed his mind

and will now walk the way of his fathers?'

It was familiar ground to either of

them. She had tried several times in the past to resolve their differences,

father and son, but the bridge strong enough to connect their two

riverbanks had long ago been washed away by swift currents. In the

end, they had simply avoided the subject of his son in their occasional

encounters.

'Our father, forgive me if I overstep

my bounds,' Iya Ibeji had responded. 'I know this matter weighs

heavy upon your heart. But what would you tell your father of blessed

memory if he asked you how many of those marks on your arms accounted

for stories you told your own son? Isn’t continuity all that

we owe our ancestry? Is no more sharing with Itangbemi a progression

of your long heritage? Is it not wiser to properly entrust the tradition

to him like it was to you, and let him worry what he does with it,

since he will be the one to answer for it?'

It was probably the most cohesively

presented statement the woman had ever made to him. He accepted

the gift without another word. It was a book of stories, his son’s

stories. Tales My Father Gave Wings, he called it. According

to one of the twins who’d read it, it was so good, the Government

had made it compulsory reading in schools all over the country.

That was supposed to be a big thing because it meant more people

may be reading it and hearing his son’s words than he had

performed to his entire lifetime on the road. Itangbemi had sent

him the book through Iya Ibeji with a message. One word really:

Forever. On her own, she added the news that his son was

a husband now. And his wife just delivered their son. Itanforijimi.

Iya Ibeji’s words dug furrows

in Itan’s already unsettled mind. The thought of seeing his

son and grandson had possessed him ever since, contributing to the

derailing of his usual plod between communities, upsetting even

further his rattled calendar. It was like he should be doing something

else now…Age was no more on his side. Time was becoming a

stranger. Maybe the ancestors were telling him to go rebuild his

fallen house. He had been looking in all the wrong places for a

way to still his troubled spirit. The answer wasn’t in familiar

places, skulking amongst familiar faces, re-enacting familiar graces…He

had done that for far too long. No one could continue his work.

Not the way he and his fathers had done it. He was out of date,

a living relic. Living the storyteller’s life was not enough

for the times anymore…Not when a tale just as compelling could

be fired to the entire world in the passage of a text-messaged second.

The unfurling of his memory and the hole in his bag was final proof

of that. He was a dying breed seeking unsuccessfully to remain relevant.

The times were changing and it was his turn to leave whatever could

not readjust behind. Maybe there was no harm in exploring his son’s

better way to record and transmit the moments and challenges

that enveloped them all.

That was the real reason for his out-of-season

presence in Ifeloju.

Itanpadeola rose to his full height,

took one of the lanterns and walked slowly to the dark far end of

the yard where a simple concrete headstone waited over a grave.

He had brought her home to Ogunbodede, her elder brother who’d

deputised as her father on the day he asked her in this same courtyard

to marry into an itinerant lifestyle shorn of even the most mundane

of human trappings. He married her and became more than a narrator

of stories to the villagers… He became family. He had brought

her body home to be buried among them. Every subsequent trip to

Ifeloju was not just to tell a story. It was an annual pilgrimage

to commune with his dead.

'Idera…Are you awake? It has

been three years since I saw our son… Iya Ibeji tells me he

has a wife and son of his own now. I thought I should come and tell

you. That is why the road steered my feet to this familiar place.

I know you are happy. This is Itangbemi’s book. See?' He placed

the paperback on the grave where the wind riffled the pages like

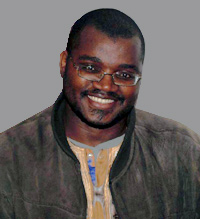

a brisk hand. 'He even put my likeness on the cover… I think

it is time to revisit the city, Idera… I’ve been a fool

for too long. Before I become a fool stuck with a bag full of empty

leaves, let me find out from him how he tells his stories in…books.

Maybe during the conversation, we will uncover how to trap the rest

of our patrimony before they become wind too.'

Itan did not wait for dawn to set

off on his journey to the city. There was a disconnected generation

out there. They grew up conversing with concrete, listening to bedlam

and inhaling exhaust fumes. He walked erect, his shoulders straight,

blazing moonlamps where his eyes used to burn. He walked, a weary

old man given wings by new promises lurking in shadows. He was going

to see what waited in those shadows… He might even encounter

the city’s stories along the way, obscured by the chaos. Itanpadeola

had no idea how they would be told, but he would ask his son…

Itangbemi would know. His son would know, after all, he had found

his own voice amidst the turmoil. He was a writer. In the end, his

son was just another Storyteller… .  |

![African Writing Online [many literatures, one voice]](http://www.african-writing.com/eight/images/logo8.png)

![]()

![]()