Adelaida de Juan

Amatoritsero Ede

Ambrose Musiyiwa

Andie Miller

Anton Krueger

Bridget McNulty

Chiedu Ezeanah

Chris Mlalazi

Chuma Nwokolo

Clara Ndyani

David Chislett

Elleke Boehmer

Emma Dawson

Esiaba Irobi

Helon Habila

Ike Okonta

James Currey

Janis Mayes

Jimmy Rage

Jumoke Verissimo

Kobus Moolman

Mary G. Berg

Molara Wood

Monica de Nyeko

Nana Hammond

Nourdin Bejjit

Olamide Awonubi

Ramonu Sanusi

Rich. Ugbede. Ali

Sefi Attah

Uzo Maxim Uzoatu

Vahni Capildeo

Veronique Tadjo

![]()

Credits:

Ntone Edjabe

Rudolf

Okonkwo

Tolu

Ogunlesi

Yomi

Ola

Molara Wood

![]()

|

|||||||

Cover Essay

Who will they bury in Fort de France? The body of Aime Fernand Cesaire, or the last memories of Negritude? For many outside the sway of Martinican and French politics, the sugestion that Negritude is to be buried may well provoke the response: was it still alive? |

|||||||

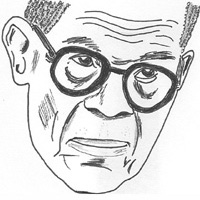

Aime Cesaire

June 26th, 1913 — 17th April, 2008 |

|||||||

A

Wreath for Cesaire |

|||||||

Up until he died on 17th April, the man for his own part was very much alive, remaining a factor in his country’s politics well into the tenth and final decade of his life. Aime Cesaire wrote the inspirational poem and coined the rallying cry under which many an African nationalist marched to independence. This man, who counted Frantz Fanon among his students at the Lycee Schoelcher, served in the trenches of that warfare in his speeches and his campaigns. He was poet and politician, playwright and essayist, marrying fellow negritudist, Suzanne Roussi in the same month that he published his most famous work (Notebook of a Return to my Native Land) in 1939. One hallmark of his life was the longevity of the philosopher-poet in political corridors. Nearly fifty years after his first success in 1945, he continued to win mayoral elections in Fort-de-France, a record that should provoke some envy from many, not least of all, the embattled Robert Mugabe. In spite of his location, Aime Cesaire was not disconnected from the African reality. In 1967, his play, Une Saison au Congo on the death of Patrice Lumumba was performed in Paris, and during his editorial stint at the literary review, Tropiques, the negritude themes of African culture retained prominence. Yet it was also true that when it was time to make the bid, he kept his eyes firmly on his own reality. In 1946, he supported the compromise of assimilation rather than independence that made Martinique an overseas department of France. In 1958, this contemporary of Charles De Gaulle supported the Communaute Francaise which bought the island more autonomy under the sway of France. Aime & the African Angst.

Many artists and writers dread the ‘ghettoization’ implicit in a career that is constricted to African-only media - even media as hallowed as the African Writers Series (may it rest in peace). Perhaps because of this, they will not exhibit in an ‘African’ Gallery, or publish in an ‘African’ series, or journal, which is destined for the ethnic corner of the bookshops that will deign to stock them. It is perhaps in the same spirit that some women will refuse the patronage of women-only anthologies or prizes (unless they are too rich to spurn): they do not want the patronage of quota-aided success. They want to triumph on a level playing-field. Even the slogans are dated… Black and Proud… Black Power…Wole Soyinka famously derided Negritude in the terms that a tiger hardly needs to proclaim its tigritude. When the decision to spurn the ‘African’ label is made early in a career, there may be the small conceit of a confidence in a talent that is substantial enough to tower, not just in an African planter box but in the jungle of the world; but there is also the long-view of the brand-making, pigeon-holing process at work in the minds of the critical and ordinary audience - because artists and writers are brands like other commodities in the marketplace. - And a brand that starts out ethnic may find it difficult to break into a more universal marketplace. Yet, all this assumes that the playing field is level. For individuals, whether professionals, artists and writers of course, the field may be more than level. Africans have won the most coveted prizes from the Nobels to the Olympics. Within the nuclear confines of individual opportunity and peculiar talent, neither skin nor geography will matter. Yet as a people, we are still very much on the outside, looking in. In all fields of endeavour, the language of engagement

has changed. It is no longer about the protest of conquest. It is

now about the conquest of protest. There is a sense that Africans

who continue to agitate for reform, for ‘freedom’, over reparations,

against globalisation, and sundry issues are trouble makers, permanent

radicals who will always find an excuse for their own failures.

For an African student on the last year of her PhD, or the early

years of a high-flying career it may seem professional suicide to

be tarred with the brush of protest in the eyes of the Western gatekeepers

of professional success. Yet, that is the viable age of protest.

A 28-year-old Achebe published Things Fall Apart, the iconic book

at the centre of an In the past, Africans who achieved a degree of penetration into elite society still saw their unalterable destiny with the masses left behind. The psychiatrist, Frantz Fanon, the prize student Aime Cesaire, the Mandelas, the Azikiwes… these were all legitimate aspirants to the ample berths of comfort available to the elite of the age. Yet, perhaps the perils they confronted - the wholesale ownership of countries by countries - had too close an affinity to the wholesale ownership of people by people. Colonialism, like slavery, manifestly, had to die. In a sense, the immoralities at the heart of 21st century problems lack that black-and-white clarity. The culprits of the present age are no longer the stock villains. Indeed, their ranks are mostly black, peopled by a raft of dictators and light-fingered administrators who hail from the same hovels as the hordes they oppress. The frontlines of the trench warfare are no longer easy to delineate, the Enemy is no longer far away and easy to villify. Nigerian poet, Olajumoke Verissimo, in her protest piece, Retrospection, which is published in this issue, rails against the IMF, the World Bank and sundry faces of imperialism, concluding, I am the welt of the world, Yet, we also live in an age when a black man whose father was Kenyan is a front-runner for the American presidency. Future negotiations between Africa and her great millstone may well be with her own spawn. The IMF delegation ladling out austere conditionalities to comatose African countries may well be headed by an African director. The waters of the race issue are certainly muddied. But it remains true that unless Africans, Diasporans or otherwise, understand and develop a consciousness within the reality of the African Condition, they will become part of the problem. There was after all, a phase in Olaudah Equiano’s inspirational life when he found himself in the boots of a slavedriver. One of the most striking areas where this consciousness is lacking is in the area of the international arms trade, that long time partner of the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade. Most African countries, like many Caribbean isles, are too small for bootstrap action, anyway. In the absence of strong federations, the notion of true independence was ever always fragile. The reality of dependency was the reality to be courted and settled for. Dependency was the everyday girl in the poem that follows, which could well be a universal Diasporan anthem to the country of residence: I’ll love you, everyday girl - The power of the rich and powerful to pauperise the relatively innocent cannot be underestimated. The beautiful vignettes in the collection of Caribbean stories titled, Cuba on the Edge, browsed in this issue, paint the picture of a country and hapless generation stunted and impoverished by an ancient quarrel with the neighbour to the north. When the character, Alborada, dies dreaming of a cup of real coffee (The Happy Death of Alborada Almanza, by Leonardo Padura Fuentes), or the character, Lisanka, improvises sanitary towels from a carefully cut up bed sheet (Women of the Federation by Francisco Garcia Gonzalez), all this 90 miles from the sump of consumer excess that is the United States, we get a sense of a stillborn revolution. Across Africa, across her Diaspora, across the world that knows the African Condition, the idea of actually reprieving suffering and dying populations is still very much a revolutionary one - that articulation of the problem and execution of its solution. Not too long ago, the Nobel Laureate, 80-year-old Jim Watson emerged from his Cold Spring Harbour laboratory to suggest that Africa’s problem was due to the fact that they were dumber than most. He was shouted out of the halls of Political Correctness and such conversations are back in the private lounges were they were before. Yet, the statistics that provide the oxygen for his racist commentaries are in the public domain. The lists of the 50 poorest countries of the world, tallied beside the list of African nations. The disproportionate representation of Diasporan Africans, relative to their proportion in the general population, in the jails, asylums and slums of their respective countries, from the United States, through Europe, to the rest of the world. It cannot be heresy to stipulate that children reared in malarial swamps on a meal a day, who attend their first school in their teens will grow up stunted physically and mentally and will not compete with Western children from whose nursery classroom the last XP computers have been ripped out in favour of Vista-designed models. Veronique Tadjo’s Blind Kingdom, whose first two chapters are reprinted here in translation, is an allegory on the African Elite. In her interview with her translator, Janis A. Mayes, she says The prime problems are not local, however, have never been local. If proof is required, we need not look beyond the last shipment from the three cornered Trans-Altantic Slave Trade — the vessel that butted vainly around southern African ports in the fortunate floodlight of world media, seeking a port through which to discharge arms to the landlocked Zimbabwe, evoking unfortunate parallels between the beleaguered Comrade, who no longer rules by popular acclaim, with any other slave-shipping potentate of historic Africa who harvests his victim with the sickle of foreign arms. It was not the imbecility of the Congolese that left Sese Seko in power over the decades of his misrule. There was an arms factor in the mix. Aime Cesaire died an ex-mayor on one of the smaller Caribbean Islands. His Negritude philosophy, his independence streak, was mediated by his country’s proximity to and dependency on France. Most of the residents of the second largest continent in the world suffer worse small-island syndromes. The ranks of the Pan-Africanists are thin. Those ruler lines drawn across sand and thicket, across clan and jungle by colonists in the European conferences of partition have acquired the impermeableness of concrete walls. Too much has been made of the end of the Slave Trade. That trade was always associated with a parallel Trade in Arms. The Trans Atlantic Slave trade would never have reached the dimensions it did, had the ships that ferried slaves to the new world not returned to Africa with the arms that established the potentates of that era. The images of the army in Myanmar crushing unarmed, red-clad monks into the ground is still fresh in memory. It is a mockery to talk about spreading democracy while spreading arms. One of the most important courtroom battles today takes place in a British courtroom. On 10th April 2008, a London high court ruled that the British Government acted illegally in stopping the Serious Frauds Office from investigating allegations that BAE had bribed the Saudis in the course of an arms deal. The story of BAE, one of the largest British companies, paying billions of pounds in bribes from Saudi Arabia to Tanzania to corruptly foist the sale of arms on countries most of whom are desperately in need of bread and books, is a story too scandalous for fiction. It is immoral for African states to spend, or be forced to spend, millions of dollars on arms in the context of their problems. From Cape to Cairo, the harvest of the arms sold by BAE and its coterie of arms dealers continue to be gathered: in wars and conflicts, in ungovernable nations, in refugees in their millions, and in children who are more versed in arms than farms. The British charities, CAAT (Campaign against Arms Trade) and Corner House deserved plaudits for bringing the lawsuit, and for their continuing work in pressing the British government on their opposition to a blanket ban on cluster bombs. If Aime died of complications attending old age, what killed Negritude then? Embarassment, more likely. On the one part were the enduring jibes, on the other, the hash made of their token independence by that generation. As we lay the ghost of Negritude willy-nilly, what are those bracing philosophies, those mind-affirming paradigms that stand in the wings? For bondage is first of all mental. Clearly, people of Aime Cesaire’s early stamp are

still needed to make sense of an even more complicated world. Men

like Afam Akeh, co-founder of Chuma Nwokolo, Jr. |

|||||||