Adelaida de Juan

Amatoritsero Ede

Ambrose Musiyiwa

Andie Miller

Anton Krueger

Bridget McNulty

Chiedu Ezeanah

Chris Mlalazi

Chuma Nwokolo

Clara Ndyani

David Chislett

Elleke Boehmer

Emma Dawson

Esiaba Irobi

Helon Habila

Ike Okonta

James Currey

Janis Mayes

Jimmy Rage

Jumoke Verissimo

Kobus Moolman

Mary G. Berg

Molara Wood

Monica de Nyeko

Nana Hammond

Nourdin Bejjit

Olamide Awonubi

Ramonu Sanusi

Rich. Ugbede. Ali

Sefi Attah

Uzo Maxim Uzoatu

Vahni Capildeo

Veronique Tadjo

![]()

Credits:

Ntone Edjabe

Rudolf

Okonkwo

Tolu

Ogunlesi

Yomi

Ola

Molara Wood

![]()

|

||||||||

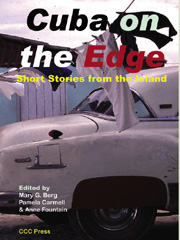

Cuba on the Edge is a collection of 31 short stories by 21 of the Caribbean islandís accomplished writers. These new translations edited by the team of Mary Berg, Pamela Carmell and Anne Fountain are a treat to the reader in English. It is difficult to find a story in the collection that is not shadowed in some fashion by the ĎSpecial PeriodĎ, the euphemism for the austerity measures forced on the besieged island by the collapse of the Soviet Union in the 90s. That shadow will have some resonance with survivors of IMF-imposed 'conditionalities'... The characters that people this collection are distracted by their jobs - or the lack of them, by their needs, and by various approximations of love and hate. Yet, humour is not hard to find. More difficult to find is a representative story to serve as sampler for the varied collection. Here is Before the Birthday Party by Adelaida Fernández de Juan

|

||||||||

| Before the Birthday Party | ||||||||

As she was going over the guest list and had gotten as far as the sixteenth child, the lights went out. She swore as usual, waited a few minutes to see if they would come back on again right away, and then since the eleven P.M. blackout continued, she grumpily began the tedious process of lighting the Chinese hurricane lamp. It was a half hour before, sweaty and irritated, she got back to the task at hand. There would be twenty-five children altogether, and if each one came with an adult, that would be fifty, but she preferred to calculate a total of one hundred, bearing in mind everyoneís craving for sweets and the recently established custom of having the whole family show up for childrenís birthday parties. To make sure she wasnít leaving out anyone important, she double-checked her list. Her sonís cousins, her own friendsí children, the grandchildren of their parentsí friends, and her bossís (as well as her husbandís bossís) nieces and nephews: no question about it, they all had to be invited. Neighborhood kids, friends from the park, her sonís classmates from school. And it would be a good idea to include the four children from the local shops: the grocerís boy, the bread distributorís two, and the new butcherís nephew. Her first estimate of around a hundred still seemed about right; it allowed some leeway for the unexpected. She went on to her second list, and she was alarmed by how little she had managed to acquire these past six months. Cardboard party boxes,* plastic glasses, spoons of some kind, a flowered tablecloth for the cake table, a lidded pail for the lemonade, little candles and paper streamers: these were all on her list, and so far she had only managed to get the tablecloth and the pail, both on loan from her cousin in San Antonio de los Baños. She adjusted the lamp as it was about to flicker out, and feeling really anxious now, she went on perusing her notebook of lists, labeled optimistically ďSonnyís Birthday.Ē Now she had to deal with the hardest part: food and drinks. The cake they were entitled to from the state, and, in case that didnít come through, a homemade cake, too, since you never know. Lemonade from the state grocery, and some instant powdered. Sheíd put a little arrow beside this last item, leading to a reminder note: she could sell the rice for dollars so she could get this. Sheíd make a cold salad with the elbow macaroni sheíd put aside four months ago. Iíd better check on that, and also on that twenty peso pineapple I froze so my husband wouldnít see it and be outraged by how much it cost. She was all set for the mayonnaise: the old woman on the corner who had high blood pressure had promised it, and, pleased, she crossed it off the list. As for the cakes, sheíd already stood in line to place the order for the state cake, down at city hall, and sheíd taken that coupon over to the other address they gave her, but she put a question mark beside it because theyíd explained to her that she could come collect it the day of the party if the eggs had arrived, if thereíd been enough gas for the oven, and if the power hadnít gone off, if the heat wasnít unbearable, Öand if it wasnít pouring rain because the woman who delivers them lives a long way away and travels by bicycle. No problem with the homemade cake, but Iíll have to sell the unrefined sugar and the scouring powder. She wrote ďMargaritaĒ beside the cake entry, since she was always ready to buy anything. Iíd better go see her tomorrow, she thought, then she focused on the drinks issue. If she couldnít get their ration quota of lemonade from the state grocery, as so often happened, then she could sell the rice to buy that powdered mix, the ďCaressesĒ brand. At this point I couldnít care less whether itís a caress or a pinch if it tastes all right and fills up the pail. The power came back on around dawn and, relieved, she moved the lamp off the dining table. Rather than continuing to agonize over all the things she still lacked, she decided to go to her bedroom to check the box of small surprises sheíd collected for the piñata and to sort out the toys sheíd bought little by little for the day of the party. There arenít enough, she fretted to herself, as she wrapped them one by one. Fourteen little rubber airplanes, all of them green, twelve whistles, ten ping-pong balls, and eight little plastic boats, three of them missing their sails. It doesnít matter, Iíll fill the piñata with the candies Katia the Russian lady makes, and with little wads of old newspapers. She tried to reassure herself, and then nervously opened the notebook again. But as she read the next list of things she still had to get, she felt her energy evaporate. Damn, sheíd managed to forget this part. Paper hats, masks, horns and balloons: people always had them. We can use condoms for balloons, and we can get the horns made by Octavio, the crazy guy with the pushcart, but what about hats and masks? Theyíre made out of cardboard, like the little boxes and like most party spoons. Reorganizing the various items eased her anxiety a little, and she grouped them, with a note: go out to the cardboard factory thatís on the road to the airport. Talk to Jorge, who sells gasoline. The last list was labeled Entertainment. Sheíd have to ask the principal of Sonnyís school for a tape of childrenís songs; she wonít turn me down if I take her a bar of soap, and we can borrow a tape player from Ariel, the son of the pilot across the way, but what about the clown? She pondered a few moments, trying to think of some clown who wouldnít tell dirty jokes, who wouldnít be so old heíd scare the kids or so young they wouldnít laugh, and she remembered that neurosurgeon who brightened up the childrenís parties at the hospital. He was doing it for free on that occasion, weíll see what he says about this time, but it seemed like a good idea, and she looked up the number of the neurological clinic so she could call the next day. When she thought she had everything all organized and knew more or less whom sheíd have to ask about each thing, she went to bed, taking care not to make a sound. She dreamed of pink paper streamers and piñatas that rained down bicycles and empty soda pop bottles. Twelve days of making deals, purchases, sales, barters, and plan changes followed, then barely twenty-four hours before the birthday party, she decided to discuss it all with her husband, just to go over everything one last time and make sure her lists were accurate. Youíre worrying too much, calm down, you act like youíre organizing a boot camp graduation ceremony for a huge class of cadets, he said. But she was so insistent, that he obliged and readied himself to listen. After all, what with meetings, people leaving the country with no notice, and being on call at the hospital, he really had no idea how all the preparations for the party were going. We donít have enough cardboard boxes or spoons, she said. At the factory they said they donít sell them there, that I should go to a party outlet. And whatís that? he asked. I donít know - see if you can find out, because Iíve looked everywhere in this neighborhood and I could only find twenty-eight boxes and nineteen spoons. Okay, tomorrow Iíll track it down, said her husband. Write ďpendingĒ next to that one. Uncle Carmelo can bring glasses on the day of the party and, since they donít make paper steamers any longer, he promised me the extra magazine pages that are left over at the print shop where he moonlights as a watchman. And what about the next item?, she asked. Yes, dear, tell me about the next disaster, answered her husband, condescendingly. No one has had new birthday candles in stock since the blackouts began. I swapped a torn towel for the bottom half of a used candle, she nearly sobbed. Calm down, calm down, Iíll get four matches and that way Sonny can blow them all out. If you stick that big fat candle in, itíll look like a funeral, and itíll make a huge hole in the cake. Go on to the next item on your agenda. Youíre making fun of me, and I wonít put up with that. Weíre talking about Sonnyís birthday party, and none of this is his fault; you know I donít want him to suffer. Fine, thatís enough, donít get all upset; tell me about the rest of it; Iím on duty all day tomorrow, and I canít stay up all night listening to your complaints. How many quarts of lemonade do we have? he asked, to make up for his impatience. Quarts, you say? At the grocery, they told me they have a nineteen-month backlog of orders, so forget about normal channels. So what are the abnormal channels? Just give me the facts quickly, without comments, sweetheart. Okay, you know I couldnít sell the rice the way Iíd planned because itís the beginning of the month so itís worth less and the going price is thirty-five cents per pound instead of the fifty Lilia had quoted me. And now that bitch is saying that fifty cents is only after the twenty-fourth of the month, and sheís telling me this when she knows I only have a day left before the party. I said no comments, he reminded her, you donít have to explain the commodities market to me. Stick to what you want me to do something about. Fine, if you want the short version, Iíll give it to you straight out. Tomorrow night you have to go to an address Iíll give you later, where thereís a lemon tree whose owners are on vacation in Júcaro or Morón, I donít remember which, but somewhere over that way, because when I was told about it I remembered the famous march from Júcaro to Morón that we heard about in History class our first year at the university. Do you remember, dear? The teacher was a short woman with blue eyes and we saw her later at the Maternity Hospital having twins. They were both boys, with low birth weights. What youíd expect with such a small mother who chain smoked, and Iíd warned her about thatÖ Please, he cut in, yawning, just tell me when and where I have to steal lemons, if you would get to the point. Sorry, I just get caught up remembering. The house is really close to here, right near Leticiaís Ė the one who sold usÖ Never mind, Iíll give you the exact address later. Can I tell you about the next thing? Sure, letís go on, if I donít get arrested for the last item. Thereís a small problem with the home-made cake. I already talked to the mining engineer who is making it for us, and heís willing to make us a huge one with fifty eggs, twenty pounds of white sugar and fourteen pounds of flour if we give him a polyester guayabera shirt. I was thinking, dear, of the one in your closet, the one that you donít much like, that peach-colored one, that you were given by the patient you operated on that night we came back from the beach, remember? A really friendly guy who was selling woven sandals like the ones your Uncle Manolo likes, that have a buckle. I know the one youíre talking about, sweetheart, he interrupted. Itís the only dress shirt I have, but if thatís the problem, itís fine with me to give it to the engineer. The problem, love, is that thatís not the hard part. The thing is that we have to go pick the cake up at the engineerís house. He lives on the eighteenth floor of that building on G Street where the elevator has been out of order since the floods last year, but I think itís worth it, because with these strong, handsome legs you have, dear, you wonít have any problem going up and down those stairs, if the result is a splendid cake for Sonny, topped with blue meringue like I wanted, that manly blue that he likes so much, right? What are you saying, dear? Youíre gone way overboard, woman! Stark, raving mad! You think Iím Mandrake the Magician? Speaking of magicians, there wonít be a clown. The neurosurgeon has gone to Miami, imagine that, he took advantage of a course he was sent to in Costa Rica, where apparently he got together with a sister who had also stayed on in San José five years ago, and from there they figured out how to make the leap. Thatís the last straw! You ask me to chase all over the city looking for party outlets no one has ever heard of; you want me to come up with four matches in a city of perpetual blackouts, to steal lemons, to give up my dress clothes, to climb stairways to heaven; and now I have to listen to the story of a neurosurgeon clown who took off for Miami? Donít yell, sweetheart, you might wake Sonny, and just think about him, dear, and his birthday party, love, and how pleased heíll be when he gets older and sees the photos. The photos! My lord, the photos! How could I forget about that! Do you think that Philosophy professor who was in Jalisco Park on Sunday taking pictures of children on the merry-go-round would be willing to come over here? He was whispering to all of us there, ďPhotos, photos, sixty cents in dollars,Ē wasnít he? Oh, darling, first thing tomorrow could you go over to the park and ask him? It wonít be more than fifteen photos, I promise you, and the money from the rice should cover it, because even if I only get thirty-five cents a pound Ö sorry, I donít want to burden you with all this Ö but tomorrow when youíre out looking for the party outlet store, you can make a little detour and go by Jalisco Park. All right? Whatís next on the list?, was the answer. Right. Thereís an art historian who has teamed up with a plastic surgeon in a juggling act thatís supposed to be spectacular. I heard about them from Olga María, the seamstress, who, incidentally, made Sonnyís new shorts and shirt outfit in exchange for a bottle of shampoo you werenít using, that red-labeled one for dry hair, you just use the green-labeled one for oily hair, right? Anyway, she said she saw the act and theyíre terrific. They juggle balls, hoops, and torches wrapped with cotton on the ends that they light when they can get alcohol, and children love it. According to her, they charge between a hundred and fifty and two hundred pesos, but ó donít have a fit ó thatís what a pair of corduroy pants costs, and I already talked to Margarita and she has agreed to buy the ones you gave me for Valentineís Day. You donít mind that, do you, dear? Anything else? murmured her husband through another yawn. Yes, dear, how do you think it all goes together? Just picture how it will be, and tell me if you donít think the patio looks marvelous with the table from our neighbor Cecilia covered with my cousinís flowered tablecloth, the engineerís blue cake, the pail full of lemonade, a plate of the Russianís candies left over after stuffing the piñata, and the walls all decorated with inflated condoms and pictures from magazines. In the center, imagine the team of jugglers with their hoods, balls, and flaming torches. What do you think, my love? A brothel scene right out of Star Wars, he pronounced. Donít tease me, darling, donít be melodramatic! If I can get some gentian violet to paint the condoms, it would brighten things up. What are you telling me now? That the circus whores had ringworm? Oh go to hell! You arenít willing to give up a thing for your sonís sake! Donít you even care about making it a happy day for him? Youíre getting hysterical; I could tell you to go to hell too, so calm down right now. Calm down? You donít even know what youíre going to give him! When are you going to get around to fixing that tricycle for him, the one thatís been out in the garage since Columbus landed? When you give me time to go looking for spokes, but why bring that up now? Arenít you satisfied with how I rigged the stove to keep the gas from coming through the oven when you turn on the only burner that works? Isnít it enough for you that I fixed up that pipe in the bathroom window so you can wash your hair with rain water? Donít you like the Chinese lamp I traded for my sugarcane harvesting boots? Have you even thought to ask how I managed to seal the leaks in the living room ceiling with modeling clay? And that day inÖ What are you laughing about? Did I say something funny? Hey, cut that out, you look like a madwoman! Donít laugh so hard; everybodyíll hear us. What are you up to, woman? Get hold of yourself, please, look what time it is. Dawn found them in each otherís arms, with just enough time for that embrace. They felt strangely joyful, as though hope, which had seemed to ebb away from them lately, was beginning to return once more. by Adelaida Fernández de Juan Translated by Mary G. Berg

|

||||||||