|

Poetry is most valuable when it is ‘honest’. It communicates

most when it springs from deep-felt emotions, however prosaic

or personal. For this reason, a poem about the commonplace may

well succeed where one about the great issues of life fail.

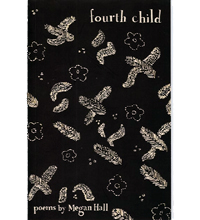

The poems in Cape Town poet, Megan Hall's poetry collection,

Fourth Child, are intensely personal,

preoccupied with the twin themes of leaving and loving.

The poems on leaving are almost always about

a death – sometimes violent, as in the maternal suicide

that is the subject of the poet in Gunshot. In this sense,

the slim volume (55 pages / 30 poems) pulsates with pain, and

the poet returns again and again to this scene in Suicide

Notes, Seed,

and – most emphatically in the title poem, Fourth

Child.

April is the cruellest

month. I should never call the month my mother left ‘kind’

The honesty of these poems have a certain

translucence. The volume carries something of an autobiographical

charge, with poems that are mostly in the first person. The emotions

of bereavement are served up here, from different viewpoints.

Many lines here are linear, unlike the more three-dimensional

poem, Real, they stray into journalese,

but are no less poignant for that. Suicide Notes,

for instance, is inspired by a New Yorker article that breaks

all suicides into 5 basic varieties. The poet concludes

I am the property to be disposed of in

your note;

it may have been the first time you owned me in this way,

then immediately bequeathed, handed me over,

intact, to the next generation.

These are acutely observed pieces and the poet’s

observation particularly comes to life in Kiss:

I bring all of myself to this kiss

on the back of your neck

as you work

…

and you nod,

continuing your own thoughts.

It is mostly in these poems on love that

the poet’s lyrical voice comes into its own. – Although

the pain of death is never far away. Indeed sometimes the imagery

of death obtrudes, jarringly, as when in the midst of the exquisite

sensuousness of the lines of Your Red and Secret Lips,

the finger of death appears:

‘Lips that I’ve taken and

tasted like sushi,

or a dead man’s finger,

…

lips that I’ve rolled

between mine

like a stone rolled in water

‘,

making for one dead line in an otherwise great

poem. There are no such lines in 14,

whose words seemed writ for speaking,

‘I’ve seen the pictures on

the screen,

rolled the knowledge over

like a pebble on my tongue.’

The rest of the lines of the conception poem

rolls off the tongue just as assuredly.

From the self-absorbed (Face

considers the poet’s mirror image in a tongue-in-cheek,

‘you never know/ which parts of you incline to treachery,

which will raise/ the flag of their own republic’)

to the cynical (Meeting at Night: two

lovers sharing a bed with little heat. ‘You are still

inside me…/ We get older stained by the meetings and leavings

of other bodies’) one of the accomplished poems in

the collection blends the two themes of death and love. Seams

is dedicated to a grandmother.

Her love is in the seams, the length

of lace.

the afternoons spent being patient

…

her love is in the dresses I’ve

outgrown but can’t toss out.’

This fusion combines with the wicked humour

of You Move Fast and To

a Friend on Getting Older, to season a collection

of honest poems anatomising a grief.

|

|

|

![]()

![]()