Jack Mapanje

Niyi Osundare

Lauri Kubuitsile

Peter Addo

N.Casely-Hayford

Kola Boof

Courttia Newland

Nii Kwei Parkes

Eusebius

McKaiser

Anietie Isong

Dike

Chukwumerije

Chinelo Achebe-

Ejeyueitche

Akin Adesokan

Tolu Ogunlesi

Adaobi Tricia

Nwaubani

Eghosa Imasuen

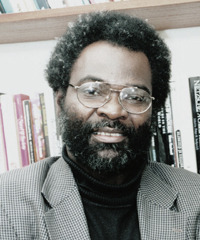

Mpalive Msiska

Roi Kwabena

Emmanuel

Sigauke

Nnedi Okoroafor-

Mbachu

George E. Clarke

Kimyia Varzi

Obemata

Uche Nduka

Amatoritsero Ede

Obododimma Oha

Leila Aboulela

James Whyle

Koye Oyedeji

Obiwu

Becky Clarke

Nike Adesuyi

Derek Petersen

Afam Akeh

Olutola Ositelu

V. Ehikhamenor

Molara Wood

Chime Hilary

Wumi Raji

Chuma Nwokolo

|

||||||||||||

Mpalive Msiska Dr. Msiska is a Senior Lecturer in English and Humanities at the Birkbeck University of London. He is a Judge for The Caine Prize for African Writing. He has previously studied in Malawi, Canada, Germany and Scotland and has taught at the Universities of Malawi, Stirling and Bath Spa. He has published conference papers, Journal articles and books, including: Wole Soyinka, (1998); Writing and Africa (Longman, 1997) Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart: A Critical Guide (Routledge, 2006) and The Quiet Chameleon: A Study of Poetry from Central Africa (Hans Zell, 1992). Forthcoming publications include, Post-Colonial Identity in Wole Soyinka, (Rodopi); He is a member of the Editorial Board of the Journal of Southern African Studies and of the Editorial Advisory Board of The Journal of African Cultural Studies. He is also an Examiner for the Commonwealth Essay Competition. |

||||||||||||

|

The term “Black-British Writing” is generally used to refer to literary texts produced by writers of African, Caribbean or Asian racial and cultural origin. The category is now employed in organising courses in Higher Education, especially in the United Kingdom, and for the publication and marketing of literary as well as critical texts in the subject area. However, like other similar literary classificatory terms, such as “Commonwealth Literature,” it has not been without its fair share of criticism. Indeed, the writer Fred D’Aguiar in an essay in Wasafiri a few years ago stated that he was opposed to the term as it was reductive of the hugely diverse concerns of the literature it purported to describe, bringing together into an incongruous composite assembly writers from radically different cultural backgrounds. Salman Rushdie had expressed similar reservations about the term “Commonwealth Literature” in his book Imaginary Homelands a few years earlier. It is clear that writers in particular do feel strongly against their work being seen largely in terms of the author’s racial biological origins instead of its intrinsic aesthetic and thematic value

|

Trees running past the window, Tickets please! Can I ask the question, The day ends as it started, I ask about the Star of Africa, They no longer fight there, |

|||||||||||