Alex Smith

Amanze Akpuda

Amatoritsero Ede

Amitabh Mitra

Ando Yeva

Andrew Martin

Aryan Kaganof

Ben Williams

Bongani Madondo

Chielozona Eze

Chris Mann

Chukwu Eke

Chuma Nwokolo

Colleen Higgs

Colleen C. Cousins

Don Mattera

Elizabeth Pienaar

Elleke Boehmer

Emilia Ilieva

Fred Khumalo

Janice Golding

Lauri Kubuitsile

Lebogang Mashile

Manu Herbstein

Mark Espin

Molara Wood

Napo Masheane

Nduka Otiono

Nnorom Azuonye

Ola Awonubi

Petina Gappah

Sam Duerden

Sky Omoniyi

Toni Kan

Uzor M. Uzoatu

Valerie Tagwira

Vamba Sherif

Wumi Raji

Zukiswa Wanner

![]()

Credits:

Ntone Edjabe

Rudolf

Okonkwo

Tolu

Ogunlesi

Yomi

Ola

Molara Wood

![]()

|

||||||

Emilia Ilieva Ilieva is an Associate Professor in Literature at Egerton University, Kenya. She has written on African literature for Encyclopedia of Post-Colonial Literatures in English (1994), The Encyclopedia of World Literature in the 20th Century (1999), The Companion to African Literatures (2000), Encyclopedia of Life Writing (2000), The Historical Companion to Postcolonial Literatures in English (2005), Encyclopedia of Activism and Social Justice, as well as other publications in Bulgaria and Russia. She has translated African fiction into Bulgarian, including Ngugi’s novel Petals of Blood.

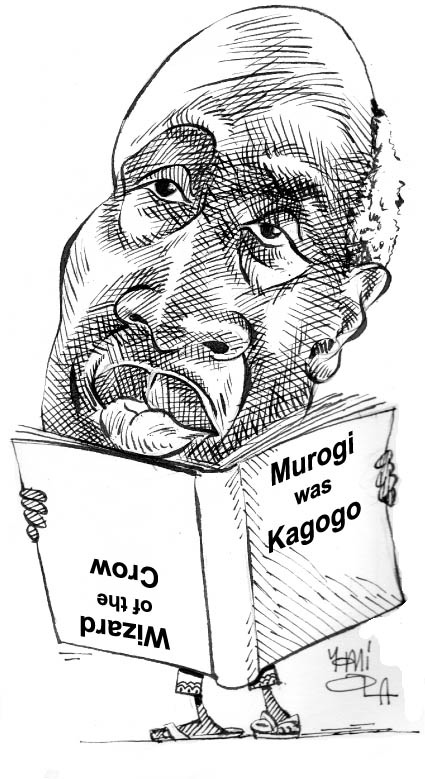

Illustration for

|

||||||

| Celebrating Ngugi wa Thiong’o at 70 | ||||||

|

||||||

The Kenyan author

Ngugi wa Thiong’o is one of Africa’s foremost writers,

thinkers and commentators; a progressive and socially engaged intellectual.

His works stand out for their unequivocal criticism of colonialism,

the subjugation of African cultures by the imperially-minded West,

and the oppression of the African masses by the ruling neocolonialist

elite.

Ngugi attended Makerere University College, Uganda, and Leeds University, UK. In 1967, he was appointed Special Lecturer in English at the University of Nairobi. He resigned his position in 1969 in protest against government interference with academic freedom at the University. After teaching at Makerere (1969–1970) and Northwestern University (1970–1971), Ngugi rejoined the University of Nairobi as Lecturer, and rose to become Associate Professor and Department Chair. He was part of a three-man successful campaign to abolish the Department of English and replace it with Department of African Literature and Languages. The argument was that literary and cultural studies in African universities had to be seen from African and not neocolonialist and Eurocentric perspectives. Starting from the late 1970s, Ngugi has appealed to African writers to abandon English (and other foreign languages) as a medium of expression, because, as a former colonial language, it perpetuates colonial values. He himself made a determined shift towards writing his creative work in his native Gikuyu. In 1994, he became the founding editor of Mutiiri, a Gikuyu social and cultural journal. In 1976, Ngugi innovatively staged a play with a Community Education and Cultural Center in the village of Kamiriithu. His co-authored Ngaahika Ndeenda (1980) (tr. I Will Marry When I Want, 1982) bravely exposed the plight of the ordinary Kenyan workers. A powerful example of people’s theatre, this venture was seen as subversive by the political establishment, and Ngugi was detained the following year. He became Amnesty International Prisoner of Conscience. As a result of international pressure on the Kenyan Government, he was released in 1978, but was denied his teaching post at the University of Nairobi. Increased government harassment forced Ngugi into exile in 1982, first in Britain and then in America. He has since taught, given lectures, and taken part in major cultural and literary forums world-wide. Ngugi is currently Distinguished Professor of English and Comparative Literature and Director of the International Center for Writing and Translation, University of California, Irvine. Ngugi’s pioneer creative works, Weep Not, Child (1964), The River Between (1965), and A Grain of Wheat (1967), focus on the colonial intrusion into the life of his people and examine the alienating effects of this onslaught on the consciousness of the colonised. Petals of Blood (1977), Caitaani Mutharaba-ini (1980) (tr. Devil on the Cross, 1982), Matigari ma Njiruungi (1986) (tr. Matigari, 1989) and Murogi wa Kagogo (2004) (tr. Wizard of the Crow, 2007), interrogate the oppressive and corrupt leadership in post-independent Kenya. Ngugi has also experimented with film production. In his essays in Decolonising the Mind (1986) and Moving the Center (1993), Ngugi underscores the importance of African culture in liberating the African people from the effects of imperialism and neocolonialism. The relationship between art and political power in African societies is examined in Writers in Politics (1997) and Penpoints, Gunpoints, and Dreams (1998). Ngugi argues that art has to be engaged and active in order to check the excesses of the modern predatory African state. These works have earned Ngugi various prizes and awards from across the world, including the 1996 Fonlon-Nichols Prize for Artistic Excellence and Human Rights, and the Nonino Prize, 2001. Ngugi is a foreign honorary member at the American Academy of Arts and Letters and has honorary life membership in the Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa (CODESRIA). A Grain of Wheat and Petals of Blood have been translated into more than thirty languages of the world. In 2004, Ngugi visited Kenya, a return he said he owed to the collective struggle of the Kenyan people to defeat the 40-year dictatorship of the Kenya African National Union (KANU) regime. The agenda of his tour, whose theme was “Reviving the Spirit”, included public lectures and launch of the first volume of his monumental novel Murogi wa Kagogo. However, a vicious attack on him and his wife by gunmen in Nairobi marred the homecoming. The Kenyan Government launched investigations into the attack and brought the matter to court. The trial ended vaguely and unsatisfactorily for Ngugi as well as for many others. Just a few weeks away – on January 5, 2008 – Ngugi turns 70. The lived years, in this case, do not signify the mere passage of time, but mark the process of the making of a colossus. Such an anniversary does not simply have to be observed; it ought to be celebrated. It is only appropriate then to take brief stock of what it is in particular we are celebrating. To begin with, Ngugi is Kenya’s – and one of Africa’s – greatest man of letters. The best of Kenyan literature so far has been concerned with the historical theme. Ngugi’s mission, more than anyone else’s, has been the writing of Kenyan history. This is so because the Kenyan understanding of the past, as Ngugi said in an early interview, “up to now has been distorted by the cultural needs of imperialism”; a factor which determined the sustained attempt by historians to demonstrate “that Kenyan people had not struggled with nature and with other men to change their natural environment and create a positive social environment” and that they “had not resisted foreign domination”. He strongly “feel[s] that Kenyan history, either pre-colonial or colonial has not yet been written”. This leads to his programmatic statement:

And since the writer, in Ngugi’s view, is the “conscience of the nation” (Sunday Nation, 16 March 1969), he sees it as his duty to engage in this essential revisionist task. Consequently, the hallmark of Ngugi’s historical fiction becomes his preoccupation with the history of the broad hitherto anonymous masses and the presentation of Kenyan history as a history of resistance to foreign domination and later forms of oppression. Ngugi sees the work of the novelist as that of sensitively registering “his encounter with history, his people’s history”. The “social, political and economic” ramifications of Africa’s involvement with “European imperialism and its changing manifestations” is what gives “impetus, shape, direction and even area of concern” to the creative practice of writers of African origin, himself included (Homecoming, 1972). The nationalist consciousness which structures Ngugi’s authorial ideology in his apprentice short stories and the first three novels is essentially a reaction against the colonising myths about Africa’s cultural inferiority. It transmutes into revolutionary consciousness in Petals of Blood, The Trial of Dedan Kimathi and the Gikuyu writings. Ngugi’s historical fiction thus conveys “irrefutable condensed experience” from generation to generation. As Solzhenitsyn said in his 1970 Nobel Lecture in Literature, when literature transmits knowledge in this “invaluable direction”, it “becomes the living memory of the nation… it preserves and kindles within itself the flame of her spent history, in a form which is safe from deformation and slander. In this way literature, together with language, protects the soul of the nation”. We celebrate Ngugi as the protector of the soul of the Kenyan nation. Contrary to the fear-stricken demonisation of Ngugi as the relentless basher of the powers that be, the writer has invariably subjected his beloved people to no lesser scrutiny than the ruling elites. The typical collocations in Ngugi’s books of historical and fictional characters have the purpose, as Carol Sicherman has observed, “to make Kenyan readers reflect on their own place in the continuum of history” (Research in African Literatures, Vol. 20, No. 3, Fall 1989). The judgement Ngugi passes both on reactionary governments and on the people themselves, in their moments of surrender to humiliation and despair and their cowardly treachery, is augmented by his concern to “suggest” a future. He has thus emerged as Kenya’s most patriotic writer. It is Ngugi’s patriotism that we celebrate today. Then, Ngugi’s unflagging commitment to the growth of African languages has been a major source of sustenance for the literatures of this continent. Like the Besht in the Hasidic legend, who was banished along with his faithful servant to a far-flung empty land, his memory erased, for having tried to hasten the coming of the Messiah, and who regained his memory and thus his powers through reciting the alphabet, so too Ngugi has remained in possession of his powers through constant engagement with the “alphabet” and the “grammar” of his people. Like Goethe, Schiller and Hölderlin – poets who, during the epoch of German classicism, elevated native German traditions to the rank of world literature – Ngugi is the writer through whom Kenyan literature has flown into the stream of world literature. There has been this accusation raised against Ngugi that he has sacrificed art to ideology, that rather than maintaining an artistic distance from the realities of life, he has been overtly political. This is hardly justified, or justifiable. As Thomas Mann argued in his famous essay, “Culture and Politics” (1939), “the political and social element are an indivisible component part of humanity”, “they are incorporated in the oneness of the problem of humanity”, “spiritually belong to it”. “It is impossible to be apolitical”, Mann postulated in another article on Goethe (1932), “we can only be antipolitical, which is to say conservative, because the spirit of politics is in its essence humanitarian revolutionary”. Those of Ngugi’s critics who felt “terrorised” by his politicisation of art should be able to see that the products of their much advertised detachment from politics and ideology are the numerous manifestations of the degeneration of life that we witness today, that we certainly witnessed on August 11th, 2004, in the brutal attack by perverts on Ngugi’s family. Just as they should have recognised the essentially metaphorical quality of the image of the revolution in Ngugi’s work, just as they should have been keen to discern that the only revolution Ngugi ever espoused is the revolution of the human spirit. The horrible events of August 11th evoked the words of assurance we find in Solzhenitsyn:

The truth is that Ngugi’s unshakeable ideological convictions are an expression of his moral steadfastness, a steadfastness not shared by many, and for that reason feared and opposed. It is the monolithic spirit that he embodies that we celebrate today. Then again, we celebrate Ngugi’s genuine humility. His essays, addresses and lectures are interspersed with the names of great men and women, particularly those who have fallen victim to powerful forces of oppression, whose contribution to the upliftment of life he extols, for ever oblivious of his own. On him, as on other outstanding writers, has weighed the obligation to divine and to express what the fallen would have wished to say. This is hardly surprising: the magnanimous spirit is always far removed from the self-opinionated posture typically struck by the narrow-minded. It is also this humility that has enabled and compelled Ngugi to move on, undeterred by detractors, incarcerators and struggles. He has felt, in the words of the Russian poet Vladimir Solov’ev:

In the literary home, many of us consider ourselves Ngugi’s children. We feel honoured, on the one hand, to have been to some extent instrumental in determining how Ngugi’s works are received in the world. On the other hand, insofar as we have gone on to become writers and scholars in our own right, we are perfect anti-specimens of the phenomenon of “anxiety of influence”. We celebrate Ngugi’s influence on us. That this influence has been of pure gold is not to be taken for granted. We know how difficult and, at times, disorienting it can be to confront the ambivalence of one’s mentors. Such was the situation, for example, in which Martin Heidegger’s students, later outstanding thinkers, found themselves after this great German philosopher of the 20th century compromised himself politically through his complicity with the Nazi regime. It is Goethe who said that it is in fact only through the personality and the character of the author that a work of art can exert an influence and can become an acquisition of culture. Ngugi has had that personality and that character. Ngugi’s presence in the world has long become a dimension and a guarantee of our own spiritual well-being and security. Certainly this is true of the best among us. The renowned Kenyan writer Marjorie Oludhe Macgoye begins the final chapter of her important novel, Coming to Birth (1986), with the description of a New Year’s Eve party in Nairobi. She depicts the strange gloom on this last day of December 1977, as the characters seek “comfort for a restlessness they could not explain”. And when the news of Ngugi’s arrest is announced, everyone realises that “there was nothing to celebrate”. Reading Ngugi’s latest novel thirty years later, Macgoye finds it possible to celebrate and to look to the future. Says she: “Ngugi is still our greatest writer and his verbal dexterity compels attention even though he has changed narrative method and his later works are translated from the Gikuyu, some by himself. He has been best known for novels and short stories redolent of down-to-earth Kenyan life but channeled chiefly through Gikuyu experience. These tend to schematise group relationships but still depict memorable characters and incidents, and often address the reader directly. The move towards the generalised fable as heralded by larger-than-life characters like Nyakinyua (in Petals) and Matigari is pushed further in Wizard of the Crow. When tortoise has beaten hare in fable there is no need for biographical detail: the story ends there. But after two characters take on the role of Wizard, there is still another 600 pages to go! So recognisable vignettes of Kenyan life fill out the moral and strike a chord overseas even when the local significance of queue-voting or night meetings is not spelled out. Obviously the major characters must fill their role as stereotypes: it is the agents who move the plot – e.g. the eloquent policeman, Vinjinia, the garbage men transformed by what they perceive as a resurrection – who link fable and narrative as memorable persons, together with recurring images of the cat, the white ache, word disease and self-induced expansion. “The apparently farcical incidents may be nearest to reality. Since the book was published cash has been showered from a helicopter and prisoners lost by police escorts without the help of donkey carts or barrows. “We miss the old Ngugi, dispensing free advice at the Heinemann office on Tuesdays or conversing with Gikuyu-speaking uncles in side-streets, but he is still accessible under the guise of Distinguished Professor. Tolstoy called War and Peace not a novel, but ‘what the author wished and was able to express’ (quoted by John Bayley on p. xii of the Signet Classic Edition, New York, 1968). Wizard is clearly what Ngugi in his 60s wishes to express, but only part of what he is able to. We look forward to more earth-bound narrative explorations in the future”. Finally, so vast is Ngugi, that it is not only

the individual that we encounter in him. I do not hesitate to say

that Ngugi represents a historical force. It is a fortunate circumstance

that we have come to a point in time when we can acknowledge the

presence of this historical force and can reach out and more towards

it until we coalesce – souls holding hands and minds no longer

agonising and malfunctioning in fear. |

||||||