Alex Smith

Amanze Akpuda

Amitabh Mitra

Ando Yeva

Andrew Martin

Aryan Kaganof

Ben Williams

Bongani Madongo

Chielozona Eze

Chris Mann

Chukwu Eke

Chuma Nwokolo

Colleen Higgs

Colleen C. Cousins

Don Mattera

Elizabeth Pienaar

Elleke Boehmer

Emilia Ilieva

Fred Khumalo

Janice Golding

Lebogang Mashile

Manu Herbstein

Mark Espin

Molara Wood

Napo Masheane

Nduka Otiono

Nnorom Azuonye

Ola Awonubi

Petina Gappah

Sam Duerden

Sky Omoniyi

Toni Kan

Uzor M. Uzoatu

Valerie Tagwira

Vamba Sherif

Wumi Raji

Zukiswa Wanner

![]()

Credits:

Ntone Edjabe

Rudolf

Okonkwo

Tolu Ogunlesi

Yomi Ola

Molara Wood

![]()

|

|||||||||||

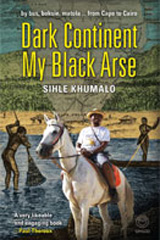

Dark Continent My Black Arse Author:

Sihle

Khumalo |

|||||||||||

| Not Yet Uhuru | |||||||||||

The world is desperate for a travel memoir about Africa by an African. Though funny in parts and occasionally enjoyable, Dark Continent my Black Arse is not that book. When you think of a travel book about Africa, chances are, it was written by a white man, or, very occasionally, a white woman. The best known travel writers, and who have subsequently become authorities on Africa, are non-Africans like Ryszard Kapuœciñski and Paul Theroux. For these writers, writing about Africa is less about a continent peopled with Africans than it is about the writers and their relationship to Africa and their non-African readers' relationships to Africa. As Binyavanga Wainaina says in his satirical essay How to Write About Africa, "[a]void having the African characters laugh, or struggle to educate their kids, or just make do in mundane circumstances. Have them illuminate something about Europe or America in Africa." And as travel writer Wendy Belcher says of her fellow Africa-focused travel writers, "[o]ur endless fascination with other cultures often amounts to little else than this: what they tell us, through imagined difference, about us. We start with ourselves (rather than Africans) because our books are ultimately about ourselves. We tend to start at the beginning (arriving), go to the middle (surviving) and then end (leaving) because our readers live outside of Africa. We detail landscapes from a protective distance to underline our readerly status as spectators rather than participants." Western travel writers (and white Africans) have written countless books in which Africa is subjected to the external gaze. Missing from the bestseller lists, from any list, is the internal gaze, a book about travel in Africa by a black African. With its catchy title and black South African author, Sihle Khumalo's Dark Continent My Black Arse could not have been more welcome. Khumalo is a South African man given to celebrating his birthday in ways his friends and family consider outrageous to celebrate his birthday. He decides that to celebrate his 30th birthday, and before he settles down to marriage with his fiancé, he will trek across Africa, from the Cape to Cairo by public transport, and write about it. Khumalo is the first black African that I have heard of who has made this popular journey and written about it, and it was thus with a singing heart that I picked up this book. I was especially encouraged by these words on the back by novelist Zakes Mda: "This is just the book we have been thirsting for: travel writing by an African adventurer who explores and tries to explain his own continent." I found Dark Continent an enjoyable and sometimes funny book. Khumalo has an eye for the absurd which makes the book laugh out loud funny in some places. His description of getting his hair plaited in Malawi had me chuckling, as did the encounters he had at various border posts and his meetings with bureaucrats, money-changers, tricksters, conmen and chancers, including agents of the law. At a border post in Ethiopia, for instance, police ask all men with leather jackets to remove them, hold the jackets to ransom while negotiations take place, and then release the jackets on a satisfactory outcome. Khumalo makes various resolutions along his journey, some reflective and honest like resolving never to use the South African derogatory word kwerekwere to describe a black African who is not South African. For all that Dark Continent was an easy and light read, I could not escape the feeling that with larger ambition, and in the hands of a writer with more curiosity and a greater affinity for people, this book could have been something special. A poster in a Facebook discussion on this book said he would have enjoyed Dark Continent more if Khumalo had not come across as "something of a jerk". Indeed, Khumalo displays several unlikeable traits. Khumalo's worldview is coloured by a gauche and unreflective misogyny. The book is littered with casual and gratuitous sexist comments: the women he meets on his travels are nothing more than the sum of their body parts, he approves of those with big bottoms, and wishes big bottoms on those with small ones; he reflects that a woman who serves him with a scowl on her face "must have been feeling menopausal", and in Ethiopia, he marvels that he is "becoming more and more like a woman, a compulsive buyer." He also appears to have something of a tin ear, faced with the raw pain of a fellow traveller who confides about her boyfriend cheating on her with her best friend, after trying to change the subject unsuccessfully, Khumalo is unable to emote beyond "Your boyfriend is a dog and your friend a whore." To avoid trouble from his fiancé who has discovered evidence of contact with another woman, he blithely tells an elaborate lie which must have caused her some anguish. I also found myself irritated by his ignorance of basic facts like the existence of the medieval Arab slave trade in East Africa, and had to remind myself that his ignorance of issues that most African schoolchildren learn in their history classes was probably a result of the parochial apartheid education system. An unlikeable personality is not necessary a death

knell for a travel book. The personality revealed in the non-fiction

of VS Naipaul for instance, is deeply unpleasant, yet he, in this

reviewer's opinion, sets the standard for travel writing. Dark Continent's

biggest flaw is not that its author is hard to warm to, but his

lapping acceptance of stereotypes, and his inability to get beneath

the surface when a surface perusal will do. Had Khumalo been more

interested in the places and people he met, had he spent a little

less time worrying about getting to the next point of his journey,

and more time on looking around him, had he spent less energy on

comparing bottom sizes, Dark Continent could have been a classic,

and the first of its kind in modern African letters. As it is, it

does not rise beyond an entertaining, funny, and sometimes irreverent

account of a South African man's adventures and some of the people

he met on a whirlwind journey from South Africa to Egypt.

|

|

||||||||||